“The principle of give and take,” said Mark Twain in a speech once, “is diplomacy – give one and take ten.” On the outside, he seems to have been right: the world – and particularly the business world – looks as if inhabited solely by takers, people who put their interests ahead of others’ needs and who’d like to get more than they give out of every interaction. In “Give and Take,” organizational psychologist Adam Grant reveals that things might not be so bleak. Though it might be indeed true that nice guys finish last, some nice guys seem to finish first as well. Get ready to discover who they are – and how to become one of them!

Takers, givers and matchers

Ability, motivation and opportunity – these are the three things that separate highly successful people from everyone else. Put otherwise, success may be described as the inevitable result of a combination of talent, dedication, and luck. Yet, according to Adam Grant, there is a fourth ingredient, one that is simultaneously critical and neglected. “Success,” writes Grant, “depends heavily on how we approach our interactions with other people. Every time we interact with another person at work, we have a choice to make: do we try to claim as much value as we can, or contribute value without worrying about what we receive in return?” Based on one’s preference for reciprocity in the workplace, Grant divides the working world into three groups of people.

- Takers. Takers live in a competitive, dog-eat-dog world, and see everyone else as a threat to their chances for success. That’s why they like to get more than they give in every interaction, constantly trying to tilt reciprocity in their favor. Not only do they make sure to get all the credit for their efforts, they are also not beyond filching other people’s contributions under their own branding. Grant claims that most of the takers aren’t cruel or anything – they are just cautious and self-protective, operating in a sort of survival mode. “If I don’t look out for myself first,” takers think, “no one will.”

- Givers. Givers stand at the opposite end of the reciprocity spectrum from givers (from takers?). A “relatively rare breed” in the workplace, givers “tilt reciprocity in the other direction, preferring to give more than they get.” Whereas takers help others only when the benefits to them outweigh the personal costs, givers help mostly when the benefits to others exceed their personal costs. “If you’re a giver at work,” explains Grant, “you simply strive to be generous in sharing your time, energy, knowledge, skills, ideas, and connections with other people who can benefit from them.”

- Matchers. In real-world circumstances, most people are neither takers nor givers, but matchers. As the term itself suggests, matchers operate on the principle of fairness. They are firm believers in tit-for-tat strategies and strive to “preserve an equal balance of giving and getting.” They’ll help whenever they can, but they’ll also expect something in return. If they don’t get it, they stop collaborating. In a word, all relationships of matchers are governed by “even exchanges of favors.”

Social interactions and success

Giving, taking, and matching are the three fundamental styles of social interaction. However, the lines between them aren’t “hard and fast,” and most people tend to shift their approaches depending on the context. For example, most of us are takers when negotiating our salaries, but givers when we need to mentor other people. Moreover, some of the people you know might be givers with their friends and families, but takers with their coworkers. Either way, we all tend to develop “a primary reciprocity style” in a given environment, meaning that very few people can be both givers and takers in the office. But which of the two is better? Or are most leaders of the business world matchers?

Givers, unsurprisingly, usually land at the bottom of the corporate ladder. But, then again, you can’t go out your way to make other people better off without sacrificing a bit of your own success, can you? Grant lists numerous studies which show that this might be as rhetorical a question as any. When compared with takers, givers earn 14% less money, have twice the risk of becoming victims of crime and are judged as 22% less powerful and dominant by the average person. Does this mean that the world is ruled by takers? Well, not really – takers and matchers usually land in the middle of the success ladder. So, who’s at the top?

Strangely enough, it’s the givers again. In most professions, givers seem to dominate both the bottom and the top of the success ladder. The least successful Californian engineers tend to give more than they receive, but the engineers with the highest productivity rates have been shown to be also mostly givers. A study of more than 600 medical students in Belgium revealed that students with high scores on statements such as “I love to help others” had both the lowest and the highest grades in the group. Finally, among the salespeople of North Carolina, both the bottom and the top performers turned out to be natural givers. To paraphrase Grant, you’ll find most of the chumps among the givers, but you’ll find most of the champs as well.

How givers, takers and matchers build networks

There are a few things that help givers reach the top of the success ladder, but perhaps none of them is as important as the social networks they create through their unique style of interaction. “Givers, takers and matchers develop fundamentally distinct networks,” writes Grant, and “their interactions within these networks have different characters and consequences.” Furthermore, he adds, “While givers and takers may have equally large networks, givers are able to produce far more lasting value through their networks, and in ways that might not seem obvious.”

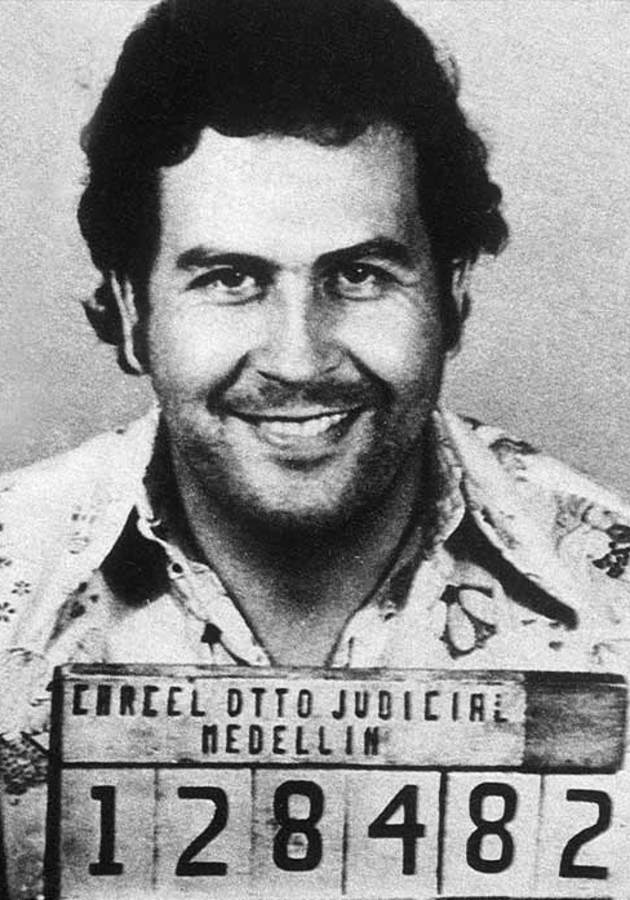

Takers are active networkers. “Dominant and controlling with subordinates,” they are “surprisingly submissive and deferential toward superiors.” Consequently, powerful people often tend to get glowing first impressions of them. Consider Kenneth Lay, the founder and chairman of Enron who died in 2006, about three months before his scheduled sentencing for taking part in the major Enron accounting scandal. He was a taker masked as a giver – until the mask wore off and he could no longer fool anybody.

Grant sums up Lay’s behavior in a memorable modification of a well-known Dutch phrase: he rose by kissing up, but fell by kicking down. So do most takers: obsessed with making good impressions upward, they treat all those that are beneath them badly. So, once they reach the top, they are left with nobody around them to trust and rely on. Even when their networks seem to be working just fine, they are actually decayed. What’s more: they are populated by people who want to punish the takers for their deplorable behavior in the past.

Most of these punishers are matchers. Matchers give takers the benefit of a doubt at first, but once they feel they have been betrayed, they start doling out punishments, and they do this in the most widespread, efficient and low-cost form there is: gossip. As more matchers start sharing their bad experiences about the takers in power, the less these takers are able to recycle their old strategies to advance and impress. Nowadays, thanks to social media, networks are far more transparent than ever before, and takers far less capable of tricking their way to the top.

Transparent networks benefit givers the most, as their social circles are, by default, a product of love and care, and not a product of self-interest. “If you set out to help others,” explains LinkedIn founder Reid Hoffman, “you will rapidly reinforce your own reputation and expand your universe of possibilities.” Silicon Valley entrepreneur Adam Rifkin – dubbed “the world’s best networker” by Fortune magazine – has always been dedicated to adding value in his relationships. His rule and advice? “You should be willing to do something that will take you five minutes or less for anybody.”

The power of powerless communication

Counterintuitively, by helping others, givers help themselves more than people actively trying to pursue their own interests in interactions with others. Otherwise stated, whereas takers operate within a win-lose framework, givers live in a win-win world. When you see reality through win-lose glasses, it is only a matter of time before the tables turn and you end up on the losing side. However, when there is no losing side to start with, you can never lose, no matter what happens.

Because givers value the perspectives and opinions of others, most of them practice a very different type of communication than the one practiced by takers. Most takers, as you might have already guessed, believe that projecting confidence and assertiveness are the two main paths toward gaining influence and prestige in the workplace. “In an effort to claim as much value as possible,” they “speak forcefully, raise their voices to assert their authority, express certainty to project confidence, promote their accomplishments, and sell with conviction and pride.” However, Grant notes, what they don’t realize is that “dominance is a zero-sum game.” That is to say, the more power one has, the less the other one is left with. And nobody wants to feel powerless in any interaction.

Knowing this, givers practice a different type of communication, dubbed by Grant “powerless communication.” Powerless communicators, he explains, “tend to speak less assertively, expressing plenty of doubt and relying heavily on advice from others. They talk in ways that signal vulnerability, revealing their weaknesses and making use of disclaimers, hedges, and hesitations.” By using hesitations such as “well,” “um,” and “uh,” hedges such as “kinda,” “sorta,” and “maybe,” or disclaimers such as “this may be a bad idea, but…,” givers signal a willingness to take other people’s opinions into their consideration and, rather than seeming lost and insecure, they leave an impression of being receptive, amenable and humane. In the long run, studies have shown, this matters far more than any kind of dominance.

Motivation maintenance, or: how not to become a doormat

If giving is so much better than taking and matching, then why are only some givers champs and others remain chumps for life? According to Grant, what separates the givers at the top from those at the bottom isn’t the strategy they employ or the communication they practice, but exhaustion. Simply put, some givers just give too much and eventually burn out. They are so selfless in their giving and care for other people that they end up losing all self-interest and becoming “pathological altruists.”

As morally laudable as this might seem, it is actually the wrong strategy both in business and in life, because humans aren’t built to be selfless givers for the long haul. By having “an unhealthy focus on others to the detriment of their own needs,” pathological altruists set themselves not just for failure and burnout, but also for physical and emotional health problems – not to mention bitterness. Chances are most of the cynics you’ve met in your life have been, at some point or another, selfless givers. Ironically, it is precisely their preference for other-interest and their lack of self-interest that transformed them into Scrooges.

In reality, self-interest and other-interest aren’t opposite ends of a single continuum, but completely independent motivations. Meaning, you can have both at the same time. “If takers are selfish and failed givers are selfless,” Grant explains, “successful givers are otherish: they care about benefiting others, but they also have ambitious goals for advancing their own interests. Selfless giving, in the absence of self-preservation instincts, easily becomes overwhelming. Being otherish means being willing to give more than you receive, but still keeping your own interests in sight, using them as a guide for choosing when, where, how, and to whom you give.”

So, to sum up, the best way to advance in business and life is to be a giver with a flexible reciprocity style. Trust and help people by default, but use your self-interest as a guide. Also, be prepared to become a matcher from time to time – especially when confronting a taker in a giver’s clothing. Grant calls this a “generous tit for tat approach.” We call it common sense.

Final notes

Described as “a brilliant, well-documented, and motivating debunking of the ‘good guys finish last’ myth” by productivity guru David Allen, “Give and Take” is an insightful and interesting read that cannot help remind one of Malcolm Gladwell’s work.

Hopefully, Grant is right in his conclusions as well, as we would never like to live in a world where he isn’t. If there’s some justice, the givers shall inherit the earth. At least for a while, it’s nice to read someone saying that they are already in power.

12min tip

“The true measure of a man,” Samuel Johnson purportedly said once, “is how he treats someone who can do him absolutely no good.” Rather than focusing on your own success and interests, try to focus on the greater good instead. At the end of the day, with one trifling exception, the world is inhabited by others. So, other people are all we got.