Being a leader is not an easy job. You need to be competent, skillful, farsighted, intelligent, commanding. And yet, as exceptional as you might be, a single mistake is all it takes to rub you out into oblivion or, even worse, to earn you a place on one or two “worst CEOs in history” lists.

David L. Dotlich and Peter C. Cairo think that there’s more to it and that it is, in fact, rarely merely about a slipup or two: most of these mistakes, in their opinion, are direct consequences of some behavioral traits.

In “Why CEOs Fail,” they analyze the 11 most common mistakes. Steer clear from them or manage them to a satisfactory level, and you might make it to the top. More importantly, you might even remain there. Find out more in our summary.

No. 1. Arrogance: you’re right and everybody else is wrong

Defined as “excessive pride” and “inflated views of self-worth,” arrogance thrives on success, confidence, and ego, and “routinely derails the best and the brightest.” Just think of Gary Wendt, Martha Stewart, Durk Jager, Robert Horton – all of them have been described as arrogant at one point or another, and none of them has managed to remain on the top. Their mistake was one and the same: they were so confident that they ended up believing they were right and that everyone who thought otherwise was merely jealous of their skills and success.

The unfortunate poster boy for this behavior is, of course, the recently released convicted felon Jeffrey Skilling, once the proud CEO of the giant that was Enron. Self-confident to a critical fault, Skilling was never short of superlatives for his company and routinely disparaged competitors such as ExxonMobil. His arrogance eventually evolved into a Darwinian belief that it is only money and fear that move the world around and that only the fittest should survive in the end, so he stopped caring for anything but success. This resulted in his lack of awareness of the numerous mistakes made due to his management style and led him to start hiding billions of dollars in debt from Enron’s investors in an unlawful attempt to cover up his slips.

You know the rest. Skilling – and a few others – were eventually convicted of federal felony charges in connection to Enron’s collapse and received appropriate prison sentences. Unfortunately, he has yet to acknowledge remorse. And that’s what arrogance does, isn’t it?

No. 2. Melodrama: you always grab the center of attention

Film critics don’t really care about melodrama for a reason: the minute the sensational statements kick in, they can already detect that they are being manipulated by a director whose objective is to appeal to their feelings rather than paint an accurate portrait of reality.

Well, the same holds true in the world of business: rather than devising a long-term strategy resistant to volatility, melodramatic leaders are more interested in flaunting their charisma and setting trends via their deals. To them, every project is “the single most important” challenge, and every employee is a VIP. This may inspire awe and respect two or three times, but inspires nothing other than annoyance and disbelief the fourth time – both inside and outside the company.

Jean-Marie Messier and Joseph Nacchio are two examples of melodramatic CEOs. More interested in displaying their brilliance before the world than boosting their company’s profits, they presided over the worst periods in the histories of Vivendi Universal and Qwest Communications. Even though, just like all melodramatic leaders, they exuded with potential and promise at the beginning.

No. 3. Volatility: your mood shifts are sudden and unpredictable

Do you know why the “good cop/bad cop” routine is still regularly used by enforcers of the law despite being parodied and unmasked by about a thousand movies (during the last decade only)? Because, expectedly, it works. Metaphorically speaking,, it is in our human nature to start cooperating with the good cop after being threatened by a bad one, either out of trust for the former or out of fear from the latter.

And this is why some leaders had practically internalized this technique – most prominently Apple’s Steve Jobs. By being bad and even derogatory to his employees when necessary but also good and enthusiastic about their work even when uncompelled by deadlines, he successfully managed to build a relationship with them in which his “controlled volatility” acted as a motivating factor, much like the good cop/bad cop routine.

Unfortunately, when a CEO gets carried away with these mood shifts, things start flying off the handle and the company inevitably suffers. That’s what happened to CNET Networks during the tenure of Halsey Minor, who is said to have been so volatile by the end that he tended to unrestrainedly praise the very same employees he had severely panned just one or two days before.

No. 4. Excessive caution: the next decision you make may be your first

Have you ever heard of a little thing called “analysis paralysis”? If not, it’s what you experienced last week at Walmart when you couldn’t choose which chocolate bar to buy for about 27 minutes. In short, you overthought something to the point that the decision-making parts of your brain completely shut down.

Of course, you didn’t risk a lot by allotting about half an hour of your life to making that “Snickers or Kit Kat” decision – except, maybe, the frustration of your spouse – but when you are the CEO of a multibillion corporation, more often than not, you don’t really have the luxury of time. Things move fast in that world, and, as a rule, the hesitant fall behind much less recoverable than the all-in gamblers and even losers.

Think of Motorola, for example. Its CEO, Chris Galvin, inherited one of the leaders of the mobile world a decade-and-some-years ago, but his overcautiousness and reluctance to leap of faith when everybody was making one – during the OS wars – resulted in Motorola first losing significant market share, and then being sold to Lenovo via Google.

No. 5. Habitual distrust: you focus on the negatives

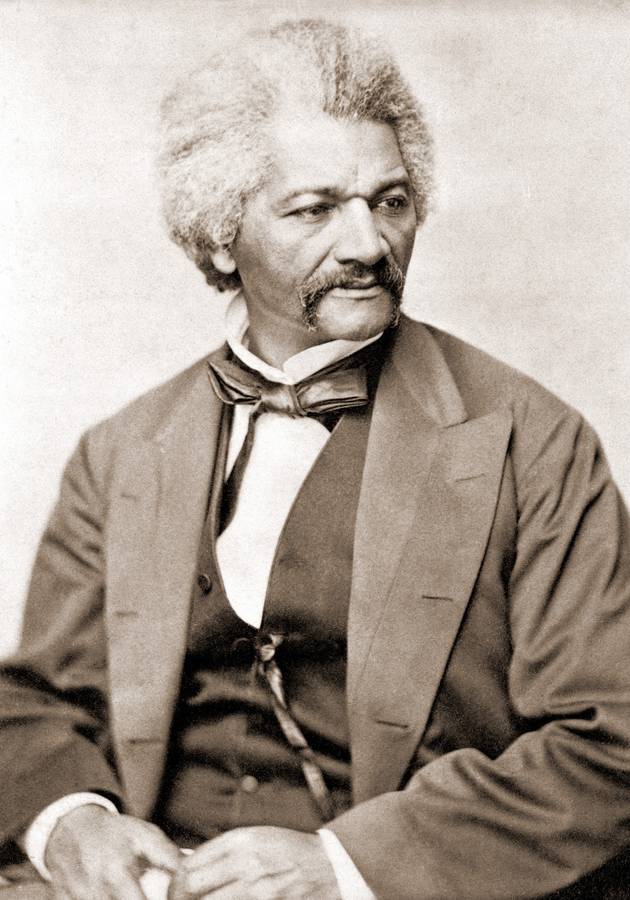

In 1972, Richard Nixon was reelected President of the United States in one of the largest electoral landslides in American history. Two years later, disgraced and discredited, he became the first (and, so far, only) American president to resign.

You can say that – between this wide approval and even wider disapproval of – Nixon stood the Watergate Scandal, but that would tell only half of the story. You see, Nixon failed as a leader of the American people, not because he taped the conversations of his adversaries – and, what’s worse, even his allies – but because he suffered from a severe character flaw: habitual distrust.

Distrustful leaders can’t lead because they unconsciously produce a legion of distrustful followers. In the sphere of leadership, paranoia breeds paranoia, and the only two possible outcomes of such a constellation of relations are totalitarianism or overthrow. So, either way, in the long run, it amounts to the latter.

No. 6. Aloofness: you disengage and disconnect

On April 1, 1999, Gordon Richard Thoman, previously senior vice president and chief financial officer of IBM, became CEO of Xerox, the first “outsider” to assume this position in one of America’s largest companies. Just 13 months later, on May 11, 2000, Thoman was forced to resign. True, many factors contributed to this outcome – internal divisions, entrenched bureaucracy, conservatism – but Dotlich and Cairo single out Thoman’s aloofness as underlining them all.

Even though Thoman wanted to properly restructure Xerox and prepare the company for the new, digital age, he didn’t bother spending time with the employees or building a bridge between him and his constantly reshuffled sales force, which eventually resulted in the company-wide condemnation of his vision and supposedly flawed reorganization strategies.

Too much contact with your employees might mean losing the allure of a withdrawn mastermind, which often describes great leaders. However, too little contact with them transforms this sometimes-necessary distance into a disadvantage. Once again, it’s all about balance.

No. 7. Mischievousness: you know that rules are only suggestions

As any creative leader would tell you, business rules are there to be broken. However, there is a fine line between breaking them for everyone’s benefit in the long run and breaking them for your own benefit in the short run. The first one is called progress; the latter is malice. They build statues of the ones capable of achieving the former; they build prisons for the ones interested in doing the latter.

While creative leaders push the limits of the field, mischievous leaders ignore even the limits prescribed by federal laws. This is what brought down Enron, Qwest, Tyco, and WorldCom – their CEOs failed to read the euphemism behind the phrase “creative accounting.” This is what brought down Bill Clinton as well: after a certain point, his charm and charisma couldn’t hide his faults anymore, and what people saw behind them was a mischievous leader who thought that some of the rules didn’t apply to him. They, of course, did – so he was out.

No. 8. Eccentricity: it’s fun to be different just for the sake of it

Some people are born as eccentrics, and some merely act like that just for the sake of being different. Think of Tesla’s Elon Musk as an example of the former group and Therion’s Elizabeth Holmes as an example of the latter. Holmes imitated Steve Jobs and was deemed a fake even before she turned out to be one – of unprecedented levels. Musk’s eccentricity is obviously a part of his character, so even his faults are seen by many people as quirky and endearing.

Either way, eccentricity, by definition, implies against-the-stream dissimilarity, and too much of it can be confusing and detaching. Paul Kazarian – the example Dotlich and Cairo describe in depth – brought Sunbeam back from the verge of bankruptcy and returned the company to profitability, but was so eccentric that he eventually had to be fired. Dubbed “mad genius” by business experts, Kazarian was an extremely eccentric and overbearing boss whose frequent tirades and erratic, irrational behavior made the lives of Sunbeam’s managers so miserable and depressing that, one day, they simply stopped caring about the success.

No. 9. Passive resistance: your silence is misinterpreted as agreement

Volatile CEOs may be unstable, but passive-resistant leaders are the real Jekyll-and-Hydes of the corporate world. “It is almost as if the passive-resistant have two personalities,” write Dotlich and Cairo, “the private and public ones. Privately, they have their own agenda, and it often doesn’t align with their public statements and actions.” Passive-resistant leaders nurture an all-understanding persona and tend to avoid conflicts by agreeing to everything in meetings, but are also predisposed to breaking their promises and stabbing people in the back when the time suits their agenda the best. Saying one thing and doing a completely different one might work in the short run – and it often does – but then again, being a leader is not a spring, but a marathon.

No. 10. Perfectionism: you get the little things right while the big things go wrong

Back in the 18th century, the French philosopher Voltaire popularized an Italian aphorism according to which “the best is the enemy of the good.” The meaning of this saying is quite obvious: you might never complete a task if you want to complete it perfectly. That is why perfectionism is not a trait of great and effective leaders. “Perfectionist CEOs,” say Dotlich and Cairo, “often ignore the big picture. They’re so wrapped up in the little things that they lose sight of all the major developments around them.” However, when it comes to leading, “good enough” is often good enough, and “perfect” is rarely a prerequisite (such is in some safety or manufacturing procedures).

No. 11. Eagerness to please: you want to win any popularity contest

It’s one thing wanting to be liked, and it is a completely different thing to structure your life and your decisions around this craving. Eager-to-please leaders do precisely that and, as a result, are often well-liked but highly ineffective. Leading presupposes making difficult decisions, and it’s every so often about risking. Populism is the exact opposite.

Final Notes

You may say that “Why CEOs Fail” oversimplifies some things here and there and that it generalizes other things in several places. You may also say that it selects traits and singles out behavior almost at will all over the place. But you can’t say that the book is not useful or that it is not readable in one breath.

A great compendium of “don’ts” and anecdotes that illustrate them succinctly, “Why CEOs Fail” – more often than not – seems more constructive than all those how-to-succeed-as-a-leader manuals. And since, in life, we prefer to add by subtraction – it gives us more perspective – we also recommend it more ardently.

12min Tip

As clichéd as it sounds, try being yourself as often as you can. Not everyone is born to become a leader, and if you try to fake your way to that kind of a position, chances are you won’t make it. At least certainly not in the long run.