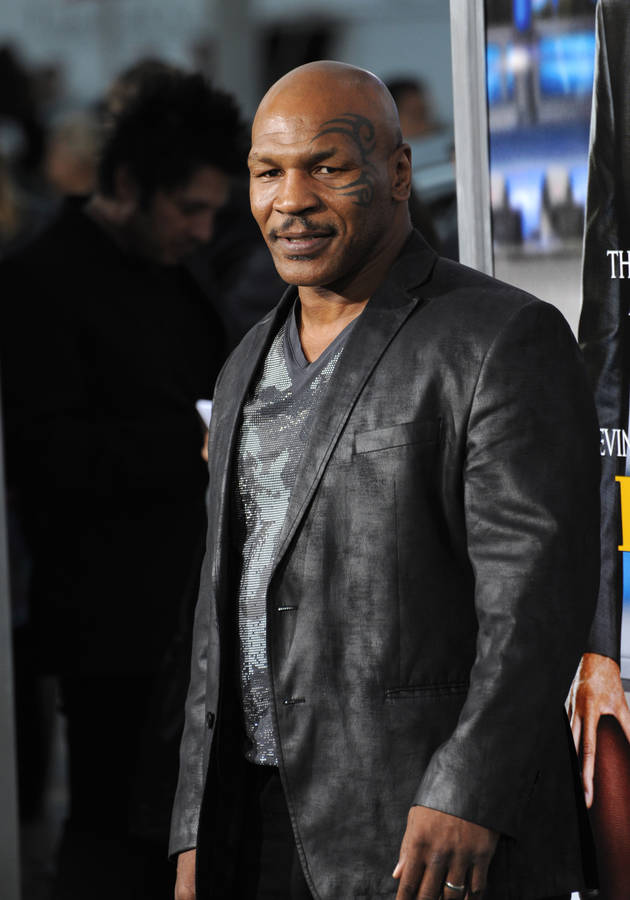

For the entire second half of the 1980s, Mike Tyson was known as “the baddest man on the planet.” At the age of 20, he became the youngest heavyweight champion in the history of boxing, and a year later, the first heavyweight boxer to simultaneously hold the WBA, WBC, and IBF titles.

Things went really downhill from then on: he quickly became “addicted to everything”; then he lost his titles to 42-to-1 underdog Buster Douglas; in 1992, he was convicted of rape and sentenced to six years in prison; released early, in 1997, he took part in one of the most infamous fights in history, from which he was disqualified for biting off Evander Holyfield’s ear; several anticlimactic knockouts later, he declared bankruptcy in 2003 – despite earning more than $300 million throughout his career.

Written with the help of Larry “Ratso” Sloman and published in 2013, “Undisputed Truth” is Tyson’s “bare-knuckled, tell-all memoir.” Just like “Iron Mike” in his prime, it overdelivers on expectations; pretty much against them, it’s more a story of redemption than a story of regret. Get ready to discover its most surprising and astonishing bits!

Mike Tyson’s first fight

Tyson grew fatherless on the streets of Brooklyn. He was an awkward, fat boy – and was often bullied by older kids for his high-pitched voice and lisp. Practically the only thing that connected him with his community was his love for pigeons. “Flying pigeons was a big sport in Brooklyn,” he remembers. “It’s unexplainable; it just gets in your blood.” He was still a child when he learned how to handle them and would later become a master of the art – something he took great pride in.

One day when he was just 7 years old – while dealing with pigeons on a roof – a boy named Barkim noticed Tyson and recruited him as a thief. Pleased with his work, he later introduced him to his gang: a Rutland Road crew called “The Cats.” During the following few years, Tyson would amass over 30 arrests for petty crimes. The bullying, however, didn’t stop.

At the age of 11 – after robbing a house with an older boy – Tyson got the hefty cut of $600. He used the bulk to buy pigeons. After discovering their hiding place, a guy named Gary Flowers and a couple of his friends tried to rob Tyson. When confronted, Gary twisted the head off one of Mike’s favorite pigeons and threw it at him, smearing the blood all over his face and shirt. Tyson had always been too scared to fight anyone before. But then and there, his anger got the better of him – and though he didn’t know how, he knocked Gary out.

Mimicking the actions of a Police Athletic League boxer well-known in the neighborhood, Tyson started skipping around the defeated opponent. And everybody started whooping and applauding him. “It was an incredible feeling even though my heart was beating out of my chest,” he remembers. “I felt good about standing up for myself, and I liked the rush of everybody applauding me and slapping fives. I guess underneath that shyness, I was always an explosive, entertaining guy.”

Becoming “Iron Mike”: transformation under Cus D’Amato

After his first fight, Tyson started gaining the respect of his peers. He began exacting revenge on his bullies for all the beatings he had taken. Older boys from other neighborhoods would come and challenge him to a fight, betting money on the outcome. In addition to stealing, fighting became a second source of income for Mike. Moreover, he started earning a fearsome reputation: he was down to fight anyone – grown men, anybody. Tyson’s family lost all hope in him, firmly convinced his life would be a life of crime.

Indeed, it wasn’t too long before he ended up in a reformatory school. And then another. And another. In 1980, when just 14, he challenged a reform school guard to a fight. This one was very different from all previous fights: the guard, a tough Irishman by the name of Bobby Stewart, was a former national amateur champ. Tyson got nothing on him and quickly got knocked down. So, after everyone left, he asked humbly: “Excuse me, sir, can you teach me how to do that?”

Bobby had an even better idea: recognizing Mike’s potential, he took the kid to Cus D’Amato, a legendary boxing trainer. After watching Tyson for just a few minutes in the ring, D’Amato told him that he would become the youngest heavyweight champion of all time – if he just listened to his advice. Mike wholeheartedly obliged, and spent the next few years learning the technical aspects of boxing, like aggressive counterpunching and the “peek-a-boo style” of defending.

When Tyson’s mother died when he was 16, D’Amato became the boy’s legal guardian. In the words of the heavyweight, he was so much more than that: a mentor, a friend, a father, a general. D’Amato taught Tyson not only how to fight but also how to gain a psychological advantage over opponents by adopting a savage persona both in and out of the ring. “Cus wanted an antisocial champion,” Tyson writes, “so I drew on the bad guys from the movies, guys like Jack Palance and Richard Widmark. I immersed myself in the role of the arrogant sociopath.” Eventually, he created the “‘Iron Mike’ persona, that monster,” even though, underneath it all, he admits to remaining that “scared kid who didn’t want to get picked on.”

The youngest heavyweight champion

D’Amato’s experiment – his “science of hurting people” – led to the desired results: the “scared Brooklyn kid” grew up to be a frightening boxer, and in the eyes of just about everyone. Almost as soon as Tyson stepped into the ring at the age of 18, he was hailed as the next heavyweight champion. He ended each of his first 19 professional fights with a knockout – 12 in the first round!

About five months after his 20th birthday, he earned a shot at the WBC title. In November 1986, he demolished Jamaican great Trevor Berbick in just two rounds on the way to his first title. Unfortunately, D’Amato wasn’t around to celebrate it with him: he died a year earlier, almost to the day. Mike didn’t take his belt off the entire night: he wore it around the lobby of the hotel, to the after-party, and even when he went out later for a drink out with his friends. He was, after all, merely 20 years old, and many of his friends were still teenagers and high schoolers. And he – well, he was the champion of the world. He was having fun.

He was also lost – entirely, immeasurably lost. “By the time I won the belt, I was truly a wrecked soul because I didn’t have any guidance,” Tyson writes. “I didn’t have Cus. I had to win the belt for Cus. We were going to do that or else we were going to die. There wasn’t any way I was leaving that ring without that belt. All that sacrifice, suffering, dedication, sacrifice, suffering. Day by day in every way. When I finally got back to my hotel room early that morning, I looked at myself in the mirror wearing that belt, and I realized that I had accomplished our mission. And now I was free.”

Controversies: sex, drugs and a reptilian

What Tyson didn’t know back then was that freedom comes with responsibilities and obligations; at the time, he felt he had neither – especially after unifying the three major heavyweight titles over his next three fights. He was on top of the world, and he started acting like it. He began drinking heavily, doing all kinds of drugs and juggling girls all around.

When Mitch Green, one of his former opponents, challenged him to a rematch one night in a Harlem street, he beat him up right then and there. To this day, he thanks God there was a big audience at the occasion, because, if not, he probably would have killed him. He was very drunk – and, in his words, he isn’t a nice drunk.

The year was 1988, and Tyson was 21, so his body could still handle the wear and tear of this kind of frivolous, fast-paced lifestyle. He knocked out Larry Holmes in four rounds, Frank Bruno in five, and Michael Spinks in a minute and thirty seconds. In between, he got married, fired his longtime trainer Kevin Rooney and hired Don King as his manager. All three would prove to be big mistakes – particularly the last one.

When speaking of King, Tyson doesn’t hold back on his disdain: “Don is a wretched, slimy reptilian. He was supposed to be my black brother, but he was just a bad man. He was going to mentor me, but all he wanted was money. He was a real greedy man. I thought I could handle somebody like King, but he outsmarted me. I was totally out of my league with that guy.”

At least in his recollection, he was outsmarted by his first wife as well: Robin Givens, then-star of the ABC sitcom “Head of the Class.” They had a tumultuous marriage that barely lasted a year, ending soon after Givens described Tyson as “manic depressive” on national TV. Givens claims – to this day – that she survived torture and pure hell alongside the heavyweight champ, but Tyson insists that her account is distorted, describing it as “the worst romance/horror novel imaginable.”

In reality – despite all of his infidelities – he maintains that he was authentically in love with her, but constantly teased and played around by Givens like a pawn in a chess game. “My social skills consisted of putting a guy in a coma,” Tyson opens up. “If I did that, I might get a good pasta meal. That’s how Cus programmed me. Every time you fight and win, you get rewarded. So maybe Robin was just what the doctor ordered. A manipulative shrew who could bring me to my knees.” Soon enough, someone else would do the same – and on Mike’s terrain.

The spectacular fall from grace

When Tyson was pitted to fight Buster Douglas in Tokyo at the beginning of 1990, he didn’t bother watching any of his opponent’s fights on video. Absorbed in arrogance, he barely even trained, spending most of his time in Japan having sex with the maids instead. His subsequent defeat against Douglas with a knockout in the tenth round is still considered one of the greatest upsets in boxing history.

To Tyson, it was also an instant career wake-up call: though already a shadow of his former self, he upped his game, and after two first-round knockouts and as many hard-fought victories over promising heavyweight Donovan Ruddock, he earned the right to regain his titles. He wouldn’t get the chance: in July 1991, he was arrested on the charge of the rape of Desiree Washington, an 18-year-old miss contestant from Rhode Island. Not even a Santeria witch doctor – with whom Tyson went to the courthouse one night with a pigeon and an egg – helped him escape the inevitable: a six-year sentence.

In prison, Tyson began studying Islam, and before too long, he converted to the faith. He also started reading a lot – anything from Will Durant’s “The Story of Civilization” through Tolstoy and Dostoyevsky to Marx, Mao, and Che Guevara. He was especially fond of Alexandre Dumas’ “The Count of Monte Cristo,” with whose main character – an honest man framed for a crime he didn’t commit – he identified passionately.

Inspired by all these figures, Tyson started seeing himself as a martyr and began planning his future success. Neither this nor the newfound faith stopped him from entering an especially risky sexual relationship with his drug counselor; similar relationships with a string of other female visitors from outside prison followed. After he was finally caught by the guards, all outside visitors were banned.

A chaotic comeback and a quiet retirement

Tyson was released from prison on parole in 1995 and quickly returned to the ring. Already in his fourth fight, he won back one of the heavyweight belts after beating Frank Bruno for the second time in his career. His next two fights would be against two-time heavyweight champion Evander Holyfield. Both fights would go down in history, but neither for reasons particularly dear to Mike. Despite being the heavy favorite, Tyson lost the first fight after an 11th-round technical knockout; in the rematch – widely considered one of the most controversial sporting events in history – he was disqualified for biting off a part of Holyfield’s ear.

To people’s eyes, this was an act of despair and impotence; in Mike’s confession, it was an act of rage and retaliation for Holyfield’s headbutts. “I was angry, I was mad, I lost my composure,” he explains. “I bit Evander Holyfield’s ear because at that moment I was enraged, and I didn’t care about fighting no more by the Marquis of Queensberry rules.” Truth be told, he didn’t care about fighting at all: he just needed the money. There was no fun in getting into the ring anymore: that part of Tyson had died the minute he stepped out of prison.

For one reason or another, almost all of his subsequent fights were controversial. In his memoir, he admits to being on drugs during most of them. To pass the mandatory drug tests, he used something he refers to as a “whizzer” – namely, a fake penis filled with someone’s clean urine. Somehow, he still earned an opportunity to fight Lennox Lewis for his heavyweight titles in 2002. Weakened by years of drugs and partying, both his body and his will let him down during the fight. He took a severe beating and was knocked out cold in the eighth round.

In Tyson’s opinion, that was the moment Iron Mike breathed his last breath. “Iron Mike had brought me too much pain, too many lawsuits, too much hate from the public, the stigma that I was a rapist, that I was public enemy No. 1,” Tyson writes. “Each punch I took from Lewis in the later rounds chipped away at that pose, that persona. And I was a willing participant in its destruction.” Not long after, Tyson filed for bankruptcy and divorced his second wife, Monica Turner, whom he had married just before the rematch with Holyfield. He retired from boxing in 2005.

In 2009, Exodus – Tyson’s 4-year-old daughter from another relationship – died after tangling her neck in a safety cord from an exercise treadmill. Tyson was determined to change his ways for good. Eleven days later, he wedded Kiki Spicer, with whom he remains married to this day. He is deeply appreciative of her and grateful for staying with him throughout the hard times. Despite intermittent battles with his demons and a few short-term relapses into addiction, he hopes to remain with her forever.

Final Notes

Unevenly edited but absorbingly written, “Undisputed Truth” is a remarkably candid memoir of raw and intense power. A must-read for any sports fan.

12min Tip

Everybody needs love and guidance from someone. Without them, even champions can end up as failures.