In 167 BC, after conquering Macedon and putting an end to the Antigonid dynasty, Roman general Lucius Aemilius visited Olympia, a small town in Elis on the Peloponnese peninsula in Greece. There, several objects and monuments attracted his attention, but none more so than a colossal gold and ivory statue of Zeus, made by the Greek sculptor Phidias about three centuries earlier. As Lucius Aemilius gazed at the statue, tears began streaming down his face, for he felt moved to his soul, as if he had seen the supreme god in person. Immediately after, he gave orders for a sacrifice to be prepared, on an ampler scale than usual, just as if he were going to perform a sacrifice in the Roman Capitol.

This wasn’t an isolated incident; it was, instead, a common sight at Olympia in ancient times. Phidias’ Statue of Zeus was not just admired, but also venerated as a sacrosanct monument unparalleled by anything made by mortals. “As Cronus is Zeus’s father in heaven,” wrote Philo of Byzantium, “so Phidias is his father in Elis. Immortal nature may have given birth to the former, but the hands of Phidias, which alone have satisfied the gods, begat the latter. Blessed is Phidias who, alone, has seen the king of the world and has recreated his astounding presence for all to see.” Since the Statue of Zeus perished in a fire in the 5th century AD, nobody can see it anymore. We can still write about it, though, and rebuild it, if not in ivory and gold, then at least in words. So, let’s.

The sanctuary of Olympia

Never really a town, Olympia in Elis was primarily a sanctuary, a giant shrine where members of the warring Greek factions could go and be guaranteed protection. Hence, it had no permanent population, save for a few priests whose jobs were to take care of the local places of worship. The most important among them were the Temple of Hera, or the Heraion, and the Temple of Zeus, or the Pelopion, named that way as it was allegedly built upon the fabled tomb of Pelops. This Pelops, in turn, was celebrated as a legendary hero, said to have given the name to the entire peninsula (Peloponnesus means “The island of Pelops”) after conquering the region in days of yore. Once he emerged victorious against his rivals, Pelops organized a chariot race as thanksgiving to the gods. It was from this funeral race that a great, still-lasting tradition sprung forth: the Olympic Games.

The first Olympic Games were organized by the authorities of Elis at the sanctuary of Olympia in the 8th century BC, with tradition (going back at least to Aristotle) dating them to 776 BC. They were imagined as – and, indeed, they became – an expression of unity, not only for the people of Peloponnesus, but for all ancient Greeks as well. During the celebration of the games, an Olympic Truce was announced to enable safe travel of both athletes and spectators from their countries to the sanctuary of Olympia and back. So important were the Games in the ancient Greek world that they were even used as a basis for the first uniform Greek calendar. Not only did the four-year interval between two successive Games, named “Olympiad,” become a unit of time in historical chronologies, but the Greek calendar itself began in 776 BC.

The Games at Olympia were usually held during the second or third full moon after the summer solstice, and unlike today’s, always retained a religious character. Modern archaeological research has unearthed evidence that the oldest structures at the site, made of wood and mud-brick, predate 776 BC by a long way, which shows that both the Games and the temples were developed on a much older, cultic basis. The most magnificent of all the shrines, that of Zeus, wasn’t built until 458 BC. Even then, it was not designed to house a congregation. Instead, on the middle day of the Games, throngs of people would gather outside before its great altar, where one hundred oxen would be slaughtered and burned as a hecatomb offering to the supreme god. In time, owing to all the sacrifices, the altar grew into a prodigious pile of ashes, and the temple came to be known, quite deservedly, as “Zeus’s second home.”

The Temple of Zeus at Olympia

The Temple of Zeus was built between 466 and 456 BC, to the design of the Elean architect Libon, in the same classical style of Doric austerity as the Parthenon of Athens. A rectangular building, the temple was oriented east-west, and set on a platform of three unequal steps. On each of its two long sides there were 13 columns, and its shorter sides held six columns each. Made of local limestone and covered with white plaster, these columns, 38 in all, held up a marble roof, above which stood elaborately sculpted scenes from Greek mythology. The western pediment, supposedly carved by Alcamenes, depicted the battle between the Centaurs and the Lapiths, and also featured a beautiful figurine of the god Apollo. On the east side, just over the entrance of the temple, Paeonius engraved a vivid portrayal of Pelops and the chariot race that gave birth to the Olympic Games.

What was inside the Olympian Temple of Zeus for the first 20 years or so of its existence was not Phidias’ statue of the supreme god, but some cult object from an older shrine at Olympia, perhaps the Temple of Hera. When, sometime around 435 BC, the authorities of Elis wanted to improve upon the focus of the temple with a suitably impressive statue, they turned their eyes to Phidias of Athens. Originally a painter, Phidias had made a great reputation for himself as a sculptor of bronze with a huge 33-foot (10-meter) statue of the goddess Athena, erected around 456 BC near the gateway to the Athenian Acropolis to memorialize the Persian Wars and the Greek victory. About a decade later, he was commissioned once again by his statesman-friend Pericles to design another sculpture of Athena, this one in gold and ivory, to be the focal point of the Parthenon.

As soon as it was finished, around 437 BC, Athena Parthenos became the most renowned cult image of Golden Age Athens. Unfortunately for both Pericles and Phidias, it also became a matter of controversy. Namely, upon completing the statue, Phidias was accused of embezzlement. Specifically, he was charged with shortchanging the amount of gold that was supposed to be used for the statue and keeping the extra for himself. At the suggestion of Pericles, Phidias carefully took off the golden robe of Athena and weighed it at a public trial. Even though this proved his innocence, his reputation was irretrievably tarnished. It didn’t help that, in the meantime, Pericles’ political opponents discovered that Phidias had impiously portrayed himself and the statesman on the shield of Athena. After these unpleasantries, the sculptor either left voluntarily or was exiled from Athens, and so became available for work elsewhere. And he was just the man they were looking for at Olympia.

Phidias at the Temple of Zeus

Despite his somewhat tarnished reputation, when Phidias arrived in Elis in 435 BC, he was still considered the greatest sculptor in all of Greece. Probably in his fifties at the time, not only had he an abundance of talent, but a wealth of experience as well. Yet, he remained speechless at the first sight of the Temple of Zeus. Even though appointed by Pericles to supervise the raising of the Parthenon itself, Phidias could feel nothing but profound appreciation for the builders of the Olympic Temple. A fragment of a poem of his, which survives to this day in an ancient anthology, has captured the sculptor’s initial, albeit austere, admiration: “While at Olympia, I kept an eye on the relations of the architect, Libon, who built the temple, with his aids, Paeonius and Alcamenes, the sculptors; and I admired much the way the architect had succeeded in attaining unity.”

At Olympia, Phidias was tasked with replicating what he had already achieved with his statue of Athena inside the Parthenon – namely, carving a grandiose sculpture out of ivory, gold and metal plates, stunning enough to immediately fix the gaze of regular visitors and casual onlookers. Doric temples were purposefully simple and streamlined so as to showcase the single statue of the god they were dedicated to, usually placed in the back, at the far end of the entrance passage. Hence, in a way, Phidias wasn’t sculpting a monument just to embellish the Olympic Temple of Zeus, but Libon before him had built the temple to provide an architectural frame for Phidias to present his immense talents. In other words, it was the temple which was built for the statue, and not the other way around.

Undaunted by the gravity of the task before him, Phidias set up his workshop almost as soon as he arrived at Olympia. Standing just outside the sanctuary, the workshop was built to the exact same dimensions as the central room of the temple, and was even furnished with similar-looking columns. When German archaeologists happened upon it in the 19th century, within it, they made the unique discovery of ivory, glass, sheet bronze, lead templates, bone tools, a bronze hammerhead, and hundreds of clay molds for glass ornaments and glass drapery details. It is possible, though not likely, that some of these molds were used by Phidias himself, for the production of Zeus’ drapery. Even if not, what the excavators discovered was, undoubtedly, the place where Phidias planned and executed all parts of his masterwork, the statue of Zeus.

The Statue of Zeus

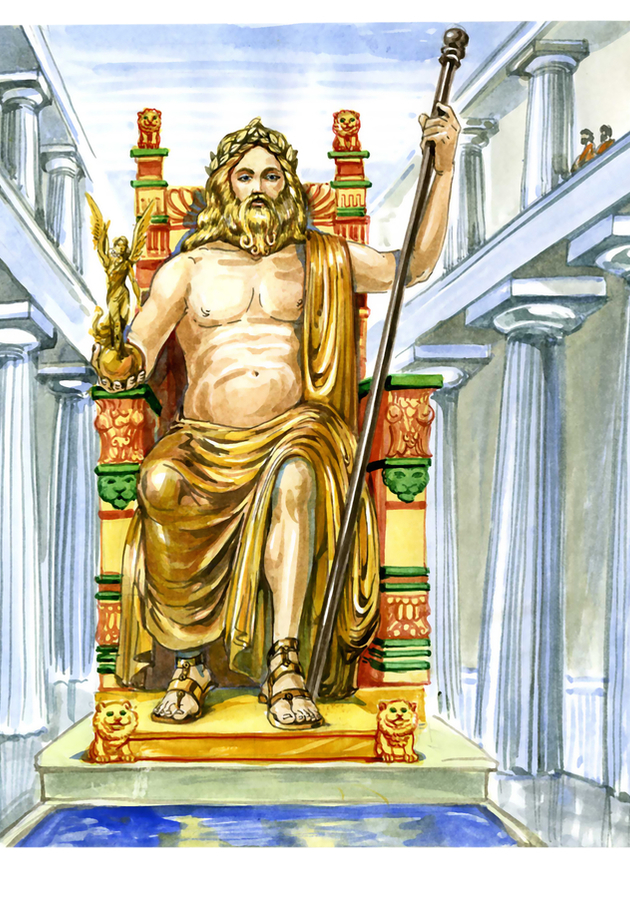

When it was completed in 430 BC, the Statue of Zeus rose to a height of 40 feet (about 12 m), as tall as a four-story building. The Athena Parthenos, which Phidias had completed just seven years before, was pretty much the same height, but his Zeus at Olympia was, against all expectations and conventions, sitting down! “Although the temple itself is very large,” bemoaned Greek geographer Strabo in the last century of the old age, “the artist has missed the proper symmetry, for he has shown Zeus seated, but almost touching the ceiling with his head, and thus giving the impression that if Zeus moved to stand up, he would unroof the temple.” But that was always going to be Phidias’ objective – to celebrate the supreme god in all his majesty and glory, and beyond that, in all his massive, irrepressible power.

It is another, later geographer by the name of Pausanias to whom we owe the most complete description of Phidias’ statue. “The god is made of gold and ivory and sits on a beautiful throne,” Pausanias wrote in his famous 2nd-century work, “Description of Greece.” “On his head, there lies a sculpted garland of olive shoots. In his right hand, he carries the goddess of Victory, which, like the statue, is also of ivory and gold; she wears a ribbon and – on her head – a garland. In the left hand of the god is a scepter, ornamented with every kind of metal, and the bird sitting on the scepter is the eagle. The sandals of the god are also of gold, as is likewise his robe. On the robe are embroidered figures of animals and the flowers of the lily. The throne is adorned with gold and with jewels, to say nothing of ebony and ivory.”

According to Pausanias, each foot of the throne carried a figure of the goddess of Victory in the form of a dancing woman, and both front legs showed Theban children ravaged by sphinxes. Under this fairly strange Egyptian motif for a Greek statue of the period, Phidias had carved a fairly common one: the shooting down of the irreverent Niobe and her children by the sibling-gods Apollo and Artemis. Further below, under the throne and its stool, the marble pedestal of Zeus carried even more scenes from Greek mythology which showed gods and heroes and the sun and the moon, all of them either made in gold or adorned with it. Finally, on the uppermost parts of the throne, just above the head of Zeus, Phidias had carved the three Graces on one side and the three Seasons on the other, all six of them named by Homer and the poets as daughters of Zeus.

Later history and destruction

Unlike other writers before him – such as the aforementioned Strabo – Pausanias wasn’t too concerned with the height and breadth of the Olympic Zeus. “Even though I know the measurements,” he wrote in his “Description of Greece,” “I won’t mention them or praise the ones who made them for all records fall far short of the impression made by a sight of the statue.” At its unveiling, Pausanias goes on, Phidias prayed to Zeus to show by sign whether the work was to his liking. Immediately a thunderbolt fell from the heavens, tearing open one part of the floor. There, on that very spot, down to the time of Pausanias and possibly all the way to the last days of the temple, a bronze jar stood to cover and honor the divine mark. In the opinion of Pausanias, that jar was a better witness to the artistic skill of Phidias than any vase drawing or papyrus scroll, however accurate or beautiful.

Not long after achieving his masterpiece, Phidias met a dire end at the hands of his former prosecutors. For reasons unknown to this day, the great sculptor went back to Athens where he was immediately imprisoned. He died soon after in jail, either by execution or just plain murder. The Temple of Zeus at Olympia didn’t fare any better. Centuries after Phidias’ death, the river Alpheus changed its course and, helped by a fire in 425 BC, destroyed nearly the entire Olympic site under a covering of mud and sand. By then, though, the statue of Zeus had been both spoiled and moved from the temple, all under the orders of Christian Roman emperors. Not that the pagan emperors didn’t try. In AD 41, Caligula ordered for the statue to be taken to pieces and moved to Rome. Just as the workmen began dismantling it, a great cackle of laughter emanated from the statue, causing the scaffoldings to collapse and the workmen to run for their lives.

What Caligula couldn’t achieve, Constantine the Great could. At the beginning of the third century, he ordered the stripping of the ample gold of the statue. There was only ivory left when, in AD 391, Theodosius I banished all pagan cults, including the Olympic Games. Robbers became frequent visitors of the temple, and the site of Phidias’ workshop was quickly turned into a church, following the plan of his building. One Roman emperor later, Lausus, a dedicated collector of antiquities and eunuch in the court of Theodosius II, was allowed to take away the gold-deprived statue of Zeus to Constantinople. That’s how the statue survived the destruction of the Olympic Temple in AD 425. Not for long, though. Just half a century later, the Palace of Lausus caught fire. The fire destroyed Lausus’ entire collection, including famous masterpieces such as the Hera of Samos, the Athena of Lindos, and the Aphrodite of Cnidus. In that majestic blaze, testify Byzantine chroniclers, perished Phidias’ masterwork too, the most beautiful realization of the classical Greeks’ idea of the father of the Gods.

Sources

Main

- Paul Jordan, Seven Wonders of the Ancient World (Routledge, 2002).

- Christopher Scarre, ed. The Seventy Wonders of the Ancient World (Thames & Hudson, 1999).

- James Grout, “The Temple of Zeus at Olympia,” Encyclopaedia Romana. [https://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/greece/hetairai/zeus.html]

- Carol Mattusch, “Zeus of Olympia,” An Encyclopedia of the History of Classical Archaeology [Nancy Thomson de Grummond, ed.] (Greenwood Press, 1996), pp. 1209-10.

Ancient

- Dio Chrysostom. Orations xii. [https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Dio_Chrysostom/Discourses/12*.html]

- Livy, History of Rome xlv.28.5. [https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/From_the_Founding_of_the_City/Book_45#28]

- Philo of Byzantium, “On the Seven Wonders of the World,” RogerPearse.com [Translation by Jean Blackwood] (August 23, 2019). [https://www.roger-pearse.com/weblog/2019/08/23/philo-of-byzantium-on-the-seven-wonders-of-the-world-an-english-translation-and-some-notes/]

- Plutarch, The Life of Pericles xxxi. [http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2008.01.0055%3Achapter%3D31].

- Strabo, Geographica viii.3.30. [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Strab.%208.3.30]

- Suetonius, Life of Caligula lvii. [https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Suetonius/12Caesars/Caligula*.html#57]

Other

- Peter D’Epiro & Mary Desmond Pinkowish, What Are the Seven Wonders of the World?: And 100 Other Great Cultural Lists (Anchor, 1998), pp. 179-187.

- Jennifer Rosenberg, “Statue of Zeus at Olympia,” ThoughtCo (August 6, 2021) [thoughtco.com/statue-of-zeus-at-olympia-1434526].

- Mark Cartwright, “Ancient Olympic Games,” World History Encyclopedia (March 13, 2018) [https://www.worldhistory.org/Olympic_Games/]