In 1987, soon after the Supreme Court ruled that Native Americans had a right to own a casino, Pulitzer Prize-winning investigative journalist David Cay Johnston got interested in the world of gambling. He applied for a job at “The Philadelphia Inquirer,” and after they greenlighted his idea, he moved to Atlantic City. And there, just a few days later, he met Donald Trump for the first time.

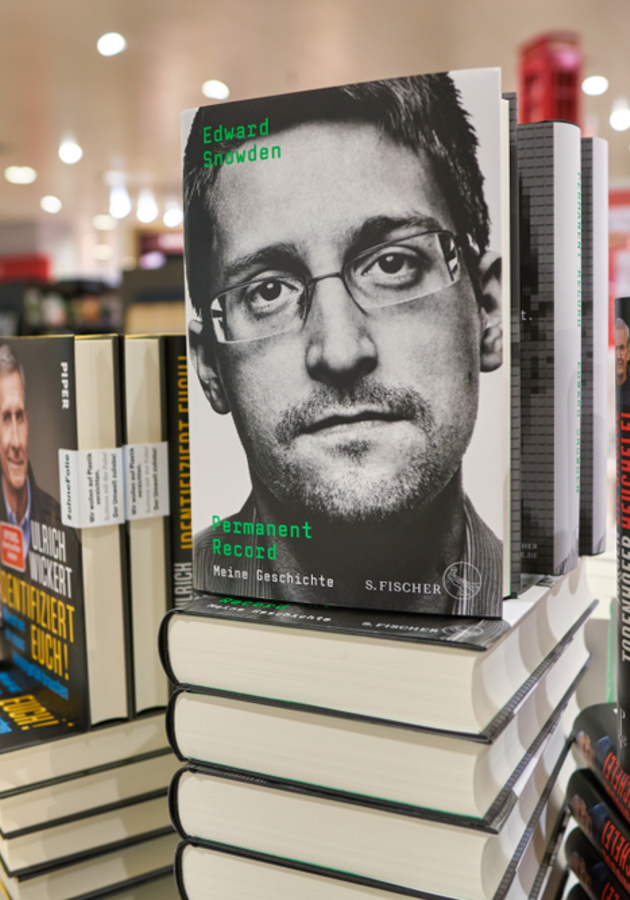

In the three decades since then, Johnston has followed him intensely and has managed to build up “a vast trove of Trump documents.” In “The Making of Donald Trump” – a book that came out just before the 2016 presidential election – he tries to make some sense of them and present a more definite portrait of the 45th president of the United States. Of course, it is unflattering – it is, after all, quite true to life.

So, get ready to hear Donald Trump’s guiding principles in life and business and prepare and discover how he has created – and manages to maintain – the myth of himself.

Donald Trump’s personal values

In 2005, Donald Trump traveled to Loveland, Colorado, to give a motivational talk in the company of his wife Melania and a violent Russian - American mobster and convicted felon named Felix Sater.

Most motivational talks, one would expect, are prepared in advance and carefully crafted. But Trump is no Zig Ziglar or Tony Robbins. “For more than an hour,” informs Johnston “Trump let fly one four-letter expletive after another. He had no prepared text, much less a rehearsed presentation…. The rambling remarks were rich with denunciations of former wives and former business associates. In vilifying a former employee, saying she had been disloyal, Trump gratuitously described her as ‘ugly as a dog.’”

It can be difficult to find a common thread in any of Trump’s utterings longer than a few words – even if they are merely tweets. Yet, the members of the Colorado audience that night in 2005 – who had, by the way, come to hear a talk by a supposed billionaire on how to succeed in life and business – were able to identify two crystal-clear recommendations. Neither sounded commonsense, nor ethical.

The first one: “trust no one, especially good employees.” They say that trust is central to market capitalism, but Trump obviously doesn’t believe this. Instead, he believes that employees will “try to fleece you,” which is why you have to be paranoid at all times. In Trump’s case, this has translated into – believe it or not – 3,500 lawsuits, some of them accusing him of civil fraud!

Trump’s second recommendation on how to succeed in business and life was even more coldhearted than the first one: “Get even,” he said then (and numerous times since). “If somebody screws you, you screw ‘em back ten times over. At least you can feel good about it. Boy, do I feel good.” So, in addition to distrust, according to Donald Trump, revenge is also a viable business strategy. And the now 45th president of the United States is not ashamed to back these claims up with evidence from his personal life.

Served hot or cold, revenge is Trump’s favorite dish

In 2007, two years after the Loveland speech, Trump published “Think Big,” his 12th book. The title of its sixth chapter: “Revenge;” its opening sentence: “I always get even.” During the following 16 pages, we discover that this is neither an exaggeration nor a character quirk, but, in fact, the guiding principle of Trump’s life, one that he is immensely proud of.

Back in the 1980s – he tells us in the book – Trump recruited an unnamed woman who had previously worked for the government for next to nothing. “I decided to make her somebody,” Trump writes. “I gave her a great job at the Trump Organization, and over time she became powerful in real estate. She bought a beautiful home.” And then, when Trump was in financial trouble in the early 1990s, he asked this woman to make a phone call to “an extremely close friend of hers” with a powerful position at a big bank. When she refused to do this, Trump fired her. Left without a job, the woman decided to start her own business that eventually failed. “I was really happy when I found that out,” writes Trump mercilessly.

“Merciless” is the right adjective here: Trump doesn’t only believe in getting even, but in hitting back harder than you were hit. For example, when Rosie O’Donnell described him as a snake-oil salesman, he bit back by calling her a pig, a degenerate, a slob, and – later, on television – disgusting inside and out. In “Think Big” he justified his behavior by claiming that he had been bullied and that he simply bullied O’Donnell back by hitting “that horrible woman right smack in the middle of the eyes.”

Donald Trump’s family values

Strangely enough, Trump’s vengeful nature isn’t only set off by disloyal employees and petty insults by actresses: in 2000, he turned on his own family as well.

On June 25, 1999, Trump’s father, Fred Trump Sr., died at the age of 93. Since his oldest son, Fred Jr., had been dead for quite some time (1981), the bulk of his fortune was distributed among his four other children: Donald, Maryanne, Robert, and Elizabeth. Fred Jr.’s children – Fred III and Mary – received only $200,000 between them. When the siblings and their mother, Linda, learned about this, they filed a lawsuit, asking for a fifth of the fortune, and asserting that Fred Sr.’s signature on his will had been “procured by fraud and undue influence” by Donald and the other surviving siblings.

Now, throughout his whole life, Fred Trump Sr. had provided every member of his family with medical insurance through his company. Fred III needed it more than anyone else because his son William – born just a day after Fred Sr.’s death – was born critically ill and needed lifelong medical care. Donald Trump knew this, so his immediate reaction to the lawsuit was ceasing all medical benefits for the little William. Considering their cost, this was “a potential death sentence.” Trump couldn’t care less. “Why should we give him medical coverage?” Trump said. “They sued my father, essentially. I’m not thrilled when someone sues my father.”

Nobody is, of course. But does cutting the medical insurance of a sickly 1-year-old adequate retribution?

Net worth and feelings (and also goats and taxes)

Even though they sound unethical and not many people would be proud of employing them, Trump’s principles – distrust and revenge – did earn him quite a lot of money. “How much?” – is an altogether different question, one that, apparently, not even Trump can answer.

In 1990 (so, around the time when he needed a favor from his female employee to save his business empire from collapse), Trump told Johnston and many other journalists that he was worth $3 billion. He told others that he was worth $2 billion more. However, a copy of his personal net worth statement obtained at the time revealed that he was probably not even a billionaire. Moreover, a report, commissioned by his bankers, “put Trump in the red by almost $300 million.”

Not really satisfied with these fluctuating figures, in his 2005 book “TrumpNation,” veteran journalist and former The New York Times editor Timothy O’Brien tried to arrive at a more accurate estimation. “Based on documents Trump had shown him and statements from three unnamed sources,” O’Brien stated, in the book, that Trump’s net worth was probably between $150 million and $250 million. Trump spent the next two years suing O’Brien and his publisher for defamation, claiming that the correct figure was between $5 billion and $6 billion and that O’Brien willfully misrepresented this, so that he could sell more books and cause irreparable damage to Trump’s reputation.

However, when asked under oath about his actual net worth, Trump didn’t give a number. “My net worth fluctuates,” he said, “and it goes up and down with markets and with attitudes and with feelings, even my own feelings.” When asked to explain how can one’s net worth fluctuate with their feelings, Trump didn’t back down but backed up this claim, saying that whenever he publicly states what he’s worth, he bases that number on his “general attitude” at the time.

There might have been another problem with Trump giving a straightforward answer to the questions about his net worth: as much as he inflates his own value for the public, he deflates it for the authorities – so that he can pay less money to the government. For example, despite claiming that he is a multibillionaire, he didn’t pay any income taxes in 1978 and 1979 – and likely every other year since then! Moreover, he managed to reduce the property tax on his golf course in Bedminster, New Jersey, to just under $1,100 a year by penning in a small herd of goats there and having it zoned as “active farmland.” Otherwise, the bill would have been a little over $80,000!

Trump’s deals: Polish brigades and mob associates

It’s one thing to squeeze out some extra dollars through the tax loopholes available to the rich, but completely another to do business with a bunch of known criminals. And Trump has done this throughout his whole life.

In 1998, Felix Sater confessed to being involved in a $40 million stock fraud scheme orchestrated by the Russian mafia and benefitting not only him, but also the Genovese and Gambino crime families. Even though he has been seen and photographed numerous times with Sater, Trump still claims that he has never met him.

He might have learned this tactic from his long-time “mentor,” “attack dog,” and “second father” – the lawyer Roy Cohn, one of the most notorious figures in postwar American history. Thanks to Cohn and his influence in the unions (via his New York mob connections), Trump was able to build his Trump Tower using ready-mix concrete (a cheap and risky option) and the immense efforts of illegal and underpaid Polish construction workers, even during the whole 1982 strike of the American cement-workers.

It was in 1982 that Trump met yet another of his infamous business associates, drug trafficker Joseph Weichselbaum. Weichselbaum was nominally responsible for helicoptering the richest clients of Trump’s casino, but – most probably – he was also in charge of getting drugs for them.

When, three years later, Weichselbaum was charged with this account, his case mysteriously moved to New Jersey and assigned to Trump’s older sister. Eventually, Weichselbaum got a year and a half – thirteen times less than the others involved in the case. Soon after his release – lo and behold! – he got his own apartment in Trump Tower, and everything was back to normal.

Maintaining the myth of Donald Trump

Throughout the years, Donald Trump managed to create an image of himself as a sort of a modern-day expert-for-all with a Midas’ touch and a no-nonsense, larger-than-life persona. Even though so many things suggest that this is obviously a façade, Trump continues to polish and sell this image, mostly by relying on two core strategies.

In the first one, he threatens to sue journalists whenever they say something incompatible with his public image. It doesn’t matter if he’s right or wrong: he just wants to discourage the investigation. He even admitted this after the case against O’Brien was dismissed. “I spent a couple of bucks on legal fees, and they spent a whole lot more. I did it to make his life miserable, which I’m happy about,” Trump bragged back then.

Trump’s second core strategy is even more vicious: he “distorts information, contradicts himself, and blocks inquiries into his conduct by journalists, law enforcement, business regulators, and other people’s lawyers.” The goal? To produce confusion and cognitive dissonance. Unfortunately, he is more than successful.

Final Notes

In an otherwise positive review, David Bromwich from The Guardian noted – in the middle of 2017, long after the calamity had already happened – that “The Making of Donald Trump” “bears the marks of having been put together under pressure to stop the election disaster.”

And, indeed, there is neither a single story here nor a chronological account of Trump’s life – just a series of 24 interrelated essays. Many stories are repeated from chapter to chapter, as are Trump’s strategies and values – which might have worked better if they served as a framing device.

Be that as it may, Johnston is an exceptional writer, and the findings he shares here are obviously the result of some exceptional research. It’s great that they’ve finally seen the light of day; it’s just too bad Johnston didn’t have enough time to edit them properly.

12min Tip

Some question how a man who explicitly believes that revenge and distrust are valuable business strategies became the leader of the American people, while others praise his ability for always managing to come out on top.

You be the judge!