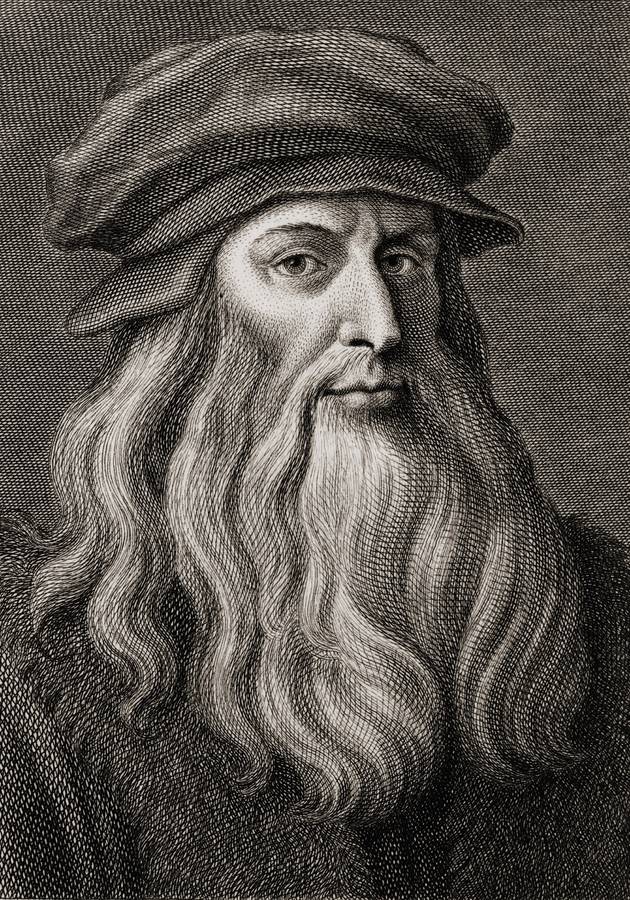

The quintessential “Renaissance man,” Leonardo da Vinci possessed unequaled talent and unbridled imagination. Perhaps “the fullest man of all time,” the scope and depth of his innumerable interests were such that he was deemed “wondrous and divine” by his contemporaries, and one can only marvel at the range of his intellect even today.

And yet, precisely because of his restless mind and inordinate ambitions, he developed a notorious and regrettable habit of merely starting ambitious projects and never finishing them. Consequently, he has influenced subsequent history almost exclusively as a painter – the subject where he first made a name as a young man in Renaissance Florence.

“Poor is the pupil who does not surpass his master”

Sometime after 1470, a few Catholic monks commissioned Andrea del Verrocchio – at the time, Florence’s most renowned sculptor, painter, and goldsmith – to create a painting of Jesus’ baptism in the church of San Salvi. Verrocchio spent the next few years of his life working on the painting, assisted by a few young artists – all members of his distinguished Florentine “bottega” (workshop). One of them was Leonardo da Vinci, then still in his 20s, but already showing promise greater than anyone before him. Because of this, Verrocchio tasked him with painting one of the four main figures in the composition: an angel holding some garments.

As time went by, the master grew more and more astonished by the results of his pupil’s work. In 1475, when the figure was finally completed, he was left speechless by the otherworldly appearance of Leonardo’s angel. Even at first sight, the angel seemed to radiate an aura of ethereality, glowing from within with celestial tenderness and unblemished beauty.

To trained eyes such as Verrocchio’s, it was obvious that the angel looked finer than any other detail of the painting – and, moreover, than anything he had ever painted before. Overwhelmed by his loveliness, the old master resolved never to touch a brush again and decided to devote the rest of his life to sculpture. Having surpassed his teacher, Leonardo left his workshop soon after and, in about 1477, set up his studio in Florence.

Leonardo’s childhood

Andrea del Verrocchio was a very good friend of Leonardo’s father, a Florentine notary of some means by the name of Piero d’Antonio. Piero decided to raise Leonardo by himself, after personally arranging for his out-of-wedlock mother – a peasant woman named Caterina – to marry a villager; at the time, this was a common practice among Florence’s wealthy elite.

In the year of Leonardo’s birth (1452), Ser Piero married a 16-year-old girl of his own rank, but both she and her even younger replacement died childless in Leonardo’s adolescent years. When Piero’s third wife finally gave him a legitimate heir, Leonardo left the household and went to live at Verrocchio’s workshop. By then, he had probably been an apprentice at the workshop for at least a few years, training to become a painter ever since his father had shown his friend Verrocchio some of Leonardo’s very first drawings.

A man of myriad interests

But the young Leonardo didn’t excel solely in art. Giorgio Vasari, a 16th-century biographer of Renaissance painters, claims that he was capable of resolving every difficult task with elegance and ease even as an infant. In only a few months studying arithmetic, he “made such progress that he raised continuous doubts and difficulties for the master who taught him and often confounded him.” And almost as soon as he started learning to play the lyre, he mastered the instrument to such an extent that nobody would dare to question his “divine gift” for music and singing.

Even so, it would be a gross understatement to say that Leonardo was just another immensely gifted boy. He was, in the words of a modern art historian, “a genius whose powerful mind will always remain an object of wonder and admiration to ordinary mortals.” Not interested in the bookish knowledge of the scholars, in an era of admiration for ancient authorities, Leonardo trusted nothing but his own eyes and experiments. With the exception of history, theology and literature, he seems to have been interested in absolutely everything – “there was nothing in nature which did not arouse his curiosity and challenge his ingenuity.”

Moreover, there was nothing Leonardo couldn’t comprehend or perform better than almost anyone of his contemporaries. This was both his blessing and his curse. Because of his “unquenchable curiosity” and ability to master every challenge in a short period of time, he quickly grew disinterested in most subjects and completed very few things in his life. His reputation as one of the greatest painters in history rests on less than 20 paintings, most of them left unfinished.

Even though he wrote more than 5,000 pages in his life, he never completed a single book. His notebooks show that he imagined and reached several engineering and scientific breakthroughs, but nobody learned anything about them until they had already been made by other people, centuries after his death. No wonder that, at the end of his life, Leonardo regretfully mourned, “I have wasted my hours.” He may have been the most gifted man in history, but, sadly, his talents and potential exceed his very few endurable accomplishments by a substantial margin.

An independent master

By the time the 29-year-old Leonardo set up a studio in Florence, his contemporaries had already begun to perceive him as “a strange and rather uncanny being.” Extraordinarily handsome and exquisitely dressed, Leonardo didn’t astound fellow citizens with his immense knowledge and exceptional skills only but also with “great physical beauty” and “more than infinite grace in every action.” He was an expert fencer and a skilled horse rider. He loved animals so much that he would often buy birds just to set them free from their cages. He was also a vegetarian.

With a reputation as an eccentric genius, it wasn’t too difficult for Leonardo to win a few commissions as an independent maestro, even in a crowded, competitive market such as 15th-century Florence. The first major one was received from the monks of San Scopeto in 1481 and it was for a chapel altarpiece: “The Adoration of the Magi.” Even though left unfinished, the painting – for which Leonardo produced thousands of sketches – is now deemed one of the greatest of the age. It already demonstrates Leonardo’s unmatched ability to softly fuse naturelike activity with abstract order – that is, to combine the demands of realism with those of design.

Artists tried achieving this ever since the beginning of the Renaissance. However, as figures do not group themselves harmoniously in reality, they struggled immensely with this problem, usually winding up with either incongruous arrangements or too rigid compositions. It seems that already in “The Adoration of the Magi,” Leonardo found a satisfactory solution: everything and everyone seems alive and in continuous movement in the painting, and yet, all figures are drawn on a strictly geometrical pattern of perspective, with the whole space divided into diminishing triangles, squares, and circles. This wasn’t an accidental success.

In his notebooks, Leonardo wrote, “A good painter has two chief objects to paint: man and the intention of his soul. The former is easy, the latter hard, for it must be expressed by gestures and the movement of the limbs.” Both in his paintings and scientific endeavors, this would always remain Leonardo’s overarching ambition: to discover the laws underlying the processes and flux of nature.

At the court of Ludovico Sforza

Leonardo abandoned “The Adoration of the Magi” after just one year and, in 1482, offered his services to Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan. He had heard that Ludovico was willing to pay good money to surround himself with exceptional men – a military engineer, an architect, a sculptor, a painter – so he decided to offer himself as all of these in one. In his 10-point letter to Ludovico – which can be best described as a Renaissance CV – Leonardo claimed that he was capable of building portable bridges and getting water out of trenches, of destroying fortresses and making big guns, and of contriving “various and endless means of military offense and defense.” Almost in a postscriptum, he added that, in times of peace, he could do in sculpture and painting, “whatever may be done, as well as any other, be he whom he may.” Even so, Leonardo got the job at the Milanese court as something altogether different: a master musician. It sounds too incredible to be true – but it almost certainly is.

It’s also true that the myriad-minded Leonardo spent most of his time at Ludovico’s court doing inconsequential things: organizing pageants, decorating stables, making jewelry for the duchess, and conceiving costumes for jousts and festivals. Fortunately, he was also commissioned to paint two pictures: “Virgin of the Rocks” and “The Last Supper.” Both are now considered masterpieces, especially the latter, which is not only the most reproduced religious painting in history but, arguably, both formally and emotionally, Leonardo’s most impressive work of art.

Unlike all previous static depictions of the event, Leonardo's painting tries to faithfully visualize the drama and excitement among Jesus’ disciples caused by Christ’s fateful words: “One of you shall betray me.” And yet, for all the lifelike movement and violent physical action, the Twelve Apostles seem naturally and harmoniously arranged into four groups of three. Moreover, their actions are painted in such a manner that the most prominent actors are easily identifiable. For example, on the left, St. Peter seems to be whispering something into St. John's ear, and he inadvertently pushes Judas forward. This makes Judas perceptively isolated from the rest, and yet he is not harshly segregated from the group as in previous depictions.

Blurred lines

In 1499, the recently crowned French King Louis XII descended upon Milan and drove out Ludovico from the city. Suddenly, Leonardo found himself uncomfortably free. After spending a few months in Venice and Mantua, he soon returned to the city of his youth, where he was now received as a great man. Young Florentine artists were excited to meet the artist who had conceived “The Adoration of the Magi” and to learn from him more about his methods of work. One of them, upon finding out that Leonardo could have an interest in his altarpiece commission, gracefully surrendered his assignment to the painter now considered the greatest in Europe.

As high as expectations were, Leonardo surpassed them all. One day, in 1501, he unveiled a large cartoon for his proposed picture of “The Virgin and Child with St. Anne.” Even though it was merely a preparatory sketch, the drawing – in the words of Vasari – “brought men, women, young and old, to see it for two days as if they were going to a solemn festival in order to gaze upon the marvels of Leonardo which stupefied the entire populace.”

This was an unprecedented reception for a cartoon, but it was more than justified. Conceived more like sculpture than two-dimensional work, the blurred lines of the cartoon create a remarkable illusion of movement. The characters of the image – Virgin Mary, Saint Anne, and Christ and John the Baptist as children – appear as if captured midmotion, in an almost photographic way.

This was another great discovery by Leonardo. Realizing that the figures of previous painters looked wooden and stiff not due to lack of precision, but precisely because of it, he started drawing the outlines less firmly and vaguer, as though disappearing into a shadow. This is Leonardo’s famous invention, which Italians call “sfumato” – the blurred outline and mellowed colors that allow one form to merge with another and always leave something to our imagination.

This technique is most evident in that most famous portrait of them all, the “Mona Lisa,” a painting which Leonardo started drawing around this time in Florence (1503), but left unfinished at his deathbed (1519). Mona Lisa’s expression is so mysterious because of Leonardo’s deft use of blurred lines around the corners of her mouth and eyes. Sometimes she seems to mock us; other times, one can catch a glimpse of sadness in her retreating smile. Its meaning is ambiguous, enigmatic, elusive – just like that of life itself.

The final brushstrokes

Leonardo didn’t start too many paintings after “Mona Lisa.” “He grows very impatient of painting, and spends most of his time on geometry,” says a 1504 note of an acquaintance. In 1506, invited by the French, Leonardo left Florence for Milan yet again, but spent most of his time there filling his notebooks with mirror-image notes and drawings.

Many of these are master studies of human and animal anatomy – some of the earliest and best in history. Others are descriptions and visualizations of a vast number of inventions, ranging from musical instruments, hydraulic pumps, and ultramodern weapons to robots, parachutes, and flying machines. Yet a third group are fascinatingly accurate scientific remarks. “The sun does not move [and] the Earth is not […] in the center of the universe,” he jotted down in a note, anticipating Copernicus and Galileo.

Unfortunately, just like in painting, Leonardo was more fertile in conception than in execution in science and engineering as well. He would have probably exerted a lot more influence on human history had it been otherwise. This way – although he was a great physician, anatomist, cartographer, astronomer, geologist, and inventor – his main contribution remains that of a painter. He spent the last three years of his life at the French court, accompanied by his favorite pupil, Francesco Melzi. When he died in 1519, Melzi wrote to Leonardo’s half-brothers informing them of the event and noted: “It would be impossible for me to express the anguish that I have suffered from this death; and while my body holds together, I shall live in perpetual unhappiness. And for good reason. The loss of such a man is mourned by all, for it is not in the power of Nature to create another.” And, indeed, five centuries later, it seems that it still hasn’t.

Sources

Main

- Charles Nicholl, Leonardo da Vinci: The Flights of Mind (Penguin Books, 2007).

- Giorgio Vasari, “The Life of Leonardo da Vinci, Florentine Painter and Sculptor,” The Lives of Artists [translation and notes by Julia Conaway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella] (Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 284-298.

- Will Durant, “Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1482),” The Story of Civilization, Vol. V: The Renaissance (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1961), pp. 199-228.

Other

- Fred S. Kleiner, “Leonardo da Vinci,” Gardner’s Art Through the Ages: A Global History, Vol. II, 14 edn. (Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2013), pp. 601-605.

- “Leonardo da Vinci,” Encyclopedia of World Biography, Vol. IX [Paula K. Byers, Suzanne M. Bourgoin, and Neil E. Walker, eds, 2nd edn] (Gale, 1998), pp. 337-340.

- E. H. Gombrich, The Story of Art (New York: Phaidon, 2016).

- Caroline Bugler et al., “The Eye Makes Fewer Mistakes Than the Mind,” The Art Book (DK, 2017), pp. 124-127.