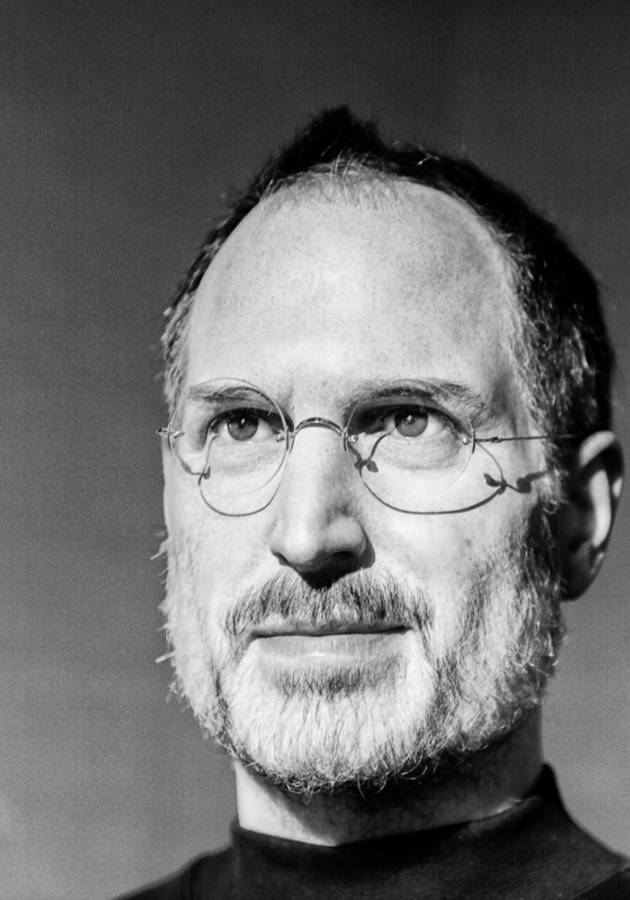

Written at the request of Mr. Apple himself, the eponymous biography of Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson is based on hundreds of interviews and unprecedented access to Steve Jobs’ life.

Adapted in the 2015 Danny Boyle blockbuster, the authorized memoir follows Jobs’ path from an adopted child to a supreme creative genius. So, get ready to get to know Jobs as you never have before – and prepare to learn what made him such an exceptional and complex visionary.

Abandoned and chosen: the drop-out messiah

Steve Paul Jobs was born on February 24, 1955, to Abdulfattah “John” Jandali, a Syrian migrant, and Joanne Schieble, a Catholic of Swiss and German descent. The two met at the University of Wisconsin, where John was a teaching assistant for a course taken by Joanne. Even before her pregnancy, her tyrannical father had threatened to cut her off completely if she continued her relationship with a Muslim, so she put Steve up for adoption. After a somewhat lengthy legal battle, he was eventually adopted by Paul and Clara Jobs, who weren’t Joanne’s first choice, two people Steve would grow up to regard as his parents “1,000%.”

Now, Paul was an engine technician and a car mechanic, so Steve was introduced to engineering from a very early age. When he was very young, Paul and Clara moved to Palo Alto, California, where he was introduced to many other things as well: from the newest advancements in technology to a namesake, Steve Wozniak. The two Steves were an odd couple: so different at first glance, so complementary after further analysis. One was a shy and secluded computer whiz kid, the other an eccentric hippie with a vision and an attitude, who regarded himself as “special” and “chosen.” Both had a fondness for pranks – and sometimes found themselves in trouble because of them.

Unsurprisingly, Jobs was often bored in school, so he rarely attended regular classes while at Reed College. Instead, he enjoyed experiencing the beauties of modern art and music and experimenting with all kinds of drugs. Years later, he would describe his senior-year LSD experiences as “one of the two or three most important things” he had ever done in his life. His father, Paul, didn’t share this view at the time: in fact, the day he found out about Steve’s LSD experiments was the only time he was ever mad at him.

Jobs dropped out of Reed after barely a year, and about a year and a half after that, he stormed into the head office of Atari and said that he would not leave it unless he got a job. He did get one, in the end – to the dismay of his co-workers, who were quickly alienated by his personality, his morals, his sense of grandeur, and the incessant need to control everything.

At Atari, Jobs was assigned to create a circuit board with the least number of TTL chips possible for an arcade video game called “Breakout” – something he didn’t really know how to do. So, he turned to Wozniak for help, promising to split the fee evenly between them. That didn’t happen even though Wozniak did a heck of a good job: even though Jobs received $5,000 for the circuit board from Atari – $100 for each chip Wozniak had managed to eliminate – he gave only $350 to his friend, telling him that his company had paid him only $700.

The dawn of a new age: the creation of Apple

Despite Jobs’ manipulative behavior, the two Steves became business partners almost immediately after meeting each other – and about five years before the foundation of the Apple Computer Company. The reason was Wozniak’s famous “blue box” – an electronic device he developed that enabled people to make long-distance calls at no cost. Jobs offered to sell it for him. It turned out that he was quite good at this, selling over 200 blue boxes for $150 each – and, this time, actually splitting the profits with his partner.

Half a decade later, in 1976, Wozniak designed something potentially even more appealing: a functional computer. However, he wasn’t that interested in selling it. Jobs thought otherwise and convinced him to co-found a company with him and another friend that would specialize in selling these computers. He also proposed the name for the company: Apple. “I was on one of my fruitarian diets,” Jobs explained to his biographer years later. “I had just come back from the apple farm. It sounded fun, spirited, and not intimidating. ‘Apple’ took the edge off the word ‘computer.’ Plus, it would get us ahead of Atari in the phone book.”

Though sold mostly to friends and a local computer dealer, the Apple I was a success: it turned profits by the end of the first month. Jobs realized that the only two things that stood between his newly founded company and global stardom were investors and proper marketing. He found both in 33-year-old semi-retired millionaire Mike Markkula, whose help would incorporate and secure valuable lines of credit to the Apple Computer Company. To Jobs’ disappointment – Markkula also recruited Mike Scott from National Semiconductor to serve as the first CEO and president of Apple. In the meantime, Wozniak was working on a greatly improved version of the company’s first computer: the Apple II.

The rise of Steve Jobs: reaching stardom

The Apple II turned out to be an astounding success, selling hundreds of thousands of units and turning the company into a major player on the market for small computers. Unsurprisingly, when the company went public in December of 1980, it sold 4.6 million shares at $22 per share, generating over $100 million and creating more than 300 millionaires by the end of the day. One of them was Steve: at the age of 25, he was suddenly worth $256 million.

However, since he had very few expensive interests besides beautifully designed objects – such as sports cars, Bösendorfer pianos, Ansel Adams prints, and Henckels knives, he was quite restless. In fact, he had already set his mind on something other than retiring or investing: revolutionizing the PC industry once and for all.

After hearing about what Xerox was working on at its Palo Alto Research Center (PARC), Jobs offered the famous corporation the right to buy $1,000,000 of Apple’s pre-IPO stock in return for three-day access to the PARC facilities. This turned out to be an amazing deal because it was there, at PARC, that Jobs saw the future of computing for the first time – everything from a demo of the mouse to the first graphical user interface (GUI).

Believing that good artists copy and great artists steal, Jobs returned from Xerox PARC with an idea for a new machine, one that would, in his words, “leave a dent in the universe.” That machine was supposed to be the Apple III, but that computer – mostly because of Jobs’ aesthetically inspired (but functionally illogical) demand to be sold without fans – completely flopped.

Then it was supposed to be the Apple Lisa – named that way after Jobs’ illegitimate daughter, whom he was reluctant to acknowledge at the time. But the project was hijacked from Jobs’ hands by the management of the company, which wasn’t interested in tolerating Jobs’ errant behavior any longer. So, Jobs assembled a renegade team of “pirates” from inside the company and started an internal competition with the Apple Lisa engineering team, building a state-of-the-art machine that would eventually become known as the Macintosh.

The first mass-market personal computer to feature a built-in screen, GUI and a mouse, the Macintosh was announced to the world by a $1.5-million-worth Ridley Scott-directed commercial, first aired during the third quarter of the Super Bowl of 1984. Now considered a masterpiece, the commercial raised the price of a single Macintosh by a whopping $500, from the initially planned $1,995 to $2,495.

Despite the hefty tag, the Macintosh got off to a great start, earning Apple a lot of money and making Jobs the man of the hour. He would have probably been named Time magazine’s “Man of the Year” as well, if not for his stubborn insistence that his daughter Lisa (as confirmed by DNA tests) wasn’t actually his. To avoid controversy, Time went out of its way and opted to name Macintosh the “Machine of the Year.”

NeXT on the agenda: to infinity and beyond

Freely giving interviews for every major magazine - while manipulating journalists into believing each of them was exclusive, Jobs enjoyed his newfound stardom too much to be bothered by the rapid decline of Macintosh sales in the second half of 1984 or the growing dissent to his ways inside Apple.

Hired by Jobs two years earlier from Pepsi to organize the Mac marketing campaign, John Sculley used the circumstances to advocate for Jobs’ removal from the position of general manager of the Macintosh division, gaining unanimous support from the Apple board of directors. Jobs didn’t take this lightly and organized a coup to oust Sculley. After this plan leaked out, Apple had Jobs stripped from all operational duties, and in September 1985, he decided to resign from the very company he had founded a decade before.

Jobs didn’t leave the corporation quietly: he took with him many capable Apple employees and immediately founded a new computer and software company. Even investing over $7 million of his own to found NeXT Inc., it wasn’t enough to feed Jobs’ voracious perfectionism. Case in point: he spent over $100,000 on the design of nothing more but the company’s rather simple logo! Because of this and similar decisions, when they finally arrived on the market, the NeXT computer workstations were just too expensive for the higher education sector for which they were primarily intended and, consequently, experienced relatively limited sales.

Fortunately, one year after leaving Apple, Jobs had also bought Lucasfilm's computer graphics division – later renamed Pixar – for the price of $10 million. He invested heavily in it as well, but, unlike NeXT, Pixar was about to change the world. In 1988, while hemorrhaging money all around, Jobs agreed to finance a computer-animated short titled “Tin Toy.” Directed by John Lasseter and highly acclaimed, “Tin Toy” won Pixar its first Academy Award, becoming the first CGI film in history to win an Oscar. More importantly, it attracted the attention of Disney, with whom Pixar was now able to partner to make the first – and, arguably, the best – entirely computer-animated feature film: “Toy Story.” It went on to gross almost $400 million worldwide in 1995, so when later that year Pixar held its IPO, Jobs became, once again, a multimillionaire overnight.

The second coming and the restoration of Apple

In the meantime, during Jobs’ absence, Sculley was running Apple into the ground. So, in 1993, he was forced to resign. Three years later, after a turbulent period, Gil Amelio was appointed as the CEO. Soon after, looking for some fresh ideas, Amelio bought Jobs’ NeXT for a staggering sum of $427 million; as part of the agreement, Jobs was brought back to the company he had co-founded.

Once he returned to Apple, Jobs immediately took as much control as he could, putting his favorite NeXT employees in the best positions possible and even convincing the directors to oust Amelio, during a boardroom coup, after Apple’s stock hit a 12-year low in the second quarter of 1997. A few months later, Jobs was formally named Apple’s interim CEO. And once that happened, he took matters into his hands.

Utterly focused on returning Apple to profitability, he terminated numerous projects and fired employees all around the company. Once a free-spirited corporate rebel, he was now a uniquely dedicated, eccentrically cooperative, and yet quite volatile executive.

Believing in “deep collaboration” and “simultaneous engineering,” he introduced several companywide processes intending to review each aspect of the product creation during development. Also, he asked the vice president for corporate materials at Compaq, Tim Cook, to join Apple and become the company’s senior vice president for worldwide operations.

The two connected almost immediately and very quickly became great friends. With the help of Cook, Jobs saved Apple from bankruptcy, turning a loss of $1 billion in 1997 into a profit of $309 million just a year later. It was only an upward spiral from thereon, thanks mostly to Jobs’ unique vision of the future and his dedication to innovation and radical change.

During the coming years, Apple’s products revolutionized so much about the way we live our lives that newer generations might have a hard time imagining a world without them. The iPod and iTunes grew out of Jobs’ realization that the internet would inevitably and irretrievably change the way people listen to music. It was vindicated very soon: in 2007, six years after its first release, the iPod accounted for half of Apple’s revenue. Three years later, in 2010, it was revealed that over half of the total global cell phone profits fell to another of Apple’s master-products: the iPhone. The same year, in April, Apple released its first iPad: the tablet computer sold 1 million units in the first month and over 15 million in just nine months!

The afterlife: Steve Jobs’ legacy

In October 2003, needing treatment for kidney stones Jobs accidentally discovered that he had pancreatic cancer. The initial prognosis was rather good: the tumor was both treatable and slow-growing. However, obstinate as ever, Jobs rejected all medical recommendations for surgery, believing that he knew and consulting nutritionists and acupuncturists instead. Unfortunately, it was the wrong strategy: cancer claimed his life eight years later.

A complicated person, he left behind him a two-sided legacy: a series of products that transformed whole industries, and a host of people hurt by his ruthlessness and vindictiveness. Fortunately, the former has already, by far, overshadowed the latter. After listing some of his flaws – such as a binary worldview, and intensity and perfectionism to a flaw – Isaacson dubs Jobs “the greatest business executive of our era, the one most certain to be remembered a century from now.”

“History will place him in the pantheon right next to Edison and Ford,” he goes on. “More than anyone else of his time, he made products that were completely innovative, combining the power of poetry and processors. With a ferocity that could make working with him as unsettling as it was inspiring, he also built the world’s most creative company. And he was able to infuse into its DNA the design sensibilities, perfectionism, and imagination that make it likely to be, even decades from now, the company that thrives best at the intersection of artistry and technology.”

Final Notes

Unlike most biographies of Steve Jobs, Walter Isaacson’s is not a hagiography, but a riveting multilayered account of a complex creative genius. And that’s why it is the best one.

So, if you want to get to know Jobs better, start with this book. You might not even need another one.

12min Tip

Allow us to quote Jobs’ 2005 commencement address at Stanford University here: “Remembering that you are going to die is the best way I know to avoid the trap of thinking you have something to lose. You are already naked. There is no reason not to follow your heart.”