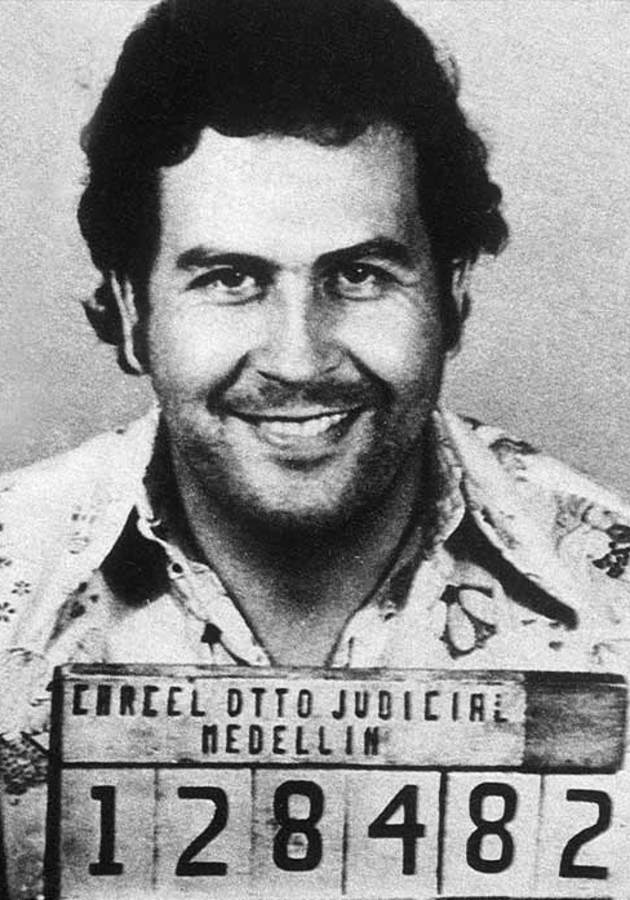

Pablo Escobar is probably one of the most famous drug lords of all time. Maybe you have even watched the Netflix series about him, “Narcos”? As Shaun Attwood now suggests, that series is not entirely truthful. The story of Pablo Escobar and the Drug Wars in the US is a lot more complicated than first meets the eye. If you want to know the true story, get ready to dive right into the terrifying world of cocaine trafficking.

Early Years

Pablo Escobar was born in 1949 on a cattle ranch in Colombia during the Violence – a ten-year civil war between the Colombian Conservative Party and the Colombian Liberal Party. Attwood says about this time, “The turmoil affected nearly every family in Colombia. It accustomed Pablo’s generation to extreme violence and the expectancy of a short and brutal life.”

Escobar was the son of Abel de Jesús Dari Escobar, a peasant farmer trading cows and horses, and Hermilda Gaviria, an elementary-school teacher. As a child, Escobar was sweet-tempered, kind to animals, and very close to his brother Roberto. However, when Escobar was seven, the guerillas came to his village, and his parents decided to hide their children under mattresses and blankets, fully expecting to be killed themselves.

At the last minute, the family was saved by soldiers arriving. The town’s survivors were escorted to a schoolhouse, past burning houses, charred bodies, and corpses hanging from lampposts. The sights of that day must have been deeply horrifying for a young Escobar. At the time, killing people with machetes was so commonplace that different slaughter methods received ornate names: One of those was The Flower Vase Cut, which meant beheading someone, and then slicing off their arms and legs, stuffing these down the neck to create a vase of body parts. The horrors of this time later resurfaced in Escobar when he kidnapped, murdered, and bombed to protect his empire.

Following this day, Pablo and his brother Roberto were sent to live with their grandmother in Medellín. She led a deeply religious household, and even into his adulthood, Escobar would always try to have a Jesus figure near him when he fell asleep. On the streets of Medellín, some of Escobar’s leadership and criminal traits started to emerge. Although he was the youngest, he would take the lead, even speaking up to the police when they took away a football the children had made out of clothes stuffed into a plastic bag.

At school, Escobar developed an interest in history, law, world politics, and poetry. He also practiced public speaking and learned about the US’ meddling in South America to enrich itself. He developed a strong sentiment of the unfairness of the poor always being the biggest victims of violence and injustice. At some point, he even claimed he would kill himself if he had not made a million pesos by age thirty.

Criminal career

Escobar felt much safer and confident on the streets and eventually dropped out of school, as he felt extremely distrustful of authority figures. He started smoking marijuana, which had a calming effect on him and enhanced his calm and quiet manner.

Escobar started dabbling in criminal enterprises, rationalizing this to himself as a form of resistance to an oppressive society. Attwood writes, “He channeled his energy into criminal activity, which ranged from selling fake lottery tickets to assaulting people. With a rifle, he walked into banks and calmly told the staff to empty their safes.”

Escobar would always remain calm and cheerful in dangerous situations which earned him respect and a loyal following. Eventually, Escobar and his gang started stealing cars, first used ones, which they would disassemble and sell the parts, and then new cars. Since it was impossible to sell these if they had been reported stolen, Escobar started offering bribes to the police. The police would issue car certificates, and Escobar could sell the cars.

Escobar also ordered the murders of people who tried to prevent his rise to power, realizing that murder was the easiest and most effective way to keep people in line.

Eventually, Escobar became involved in contraband. Contrary to what the Netflix series “Narcos” may want you to believe, Escobar was not the boss. He worked for a powerful contraband kingpin and specialized in smuggling cigarettes. He gave half of his salary to his workers, which not only earned him respect but also the nickname “El Patrón” or “the Boss.”

Cocaine trafficking

The way in which Escobar ended up in the cocaine business is also falsely portrayed in “Narcos.” He and his cousin Gustavo were introduced to suppliers of cocaine paste by the Cockroach in Peru. At the time, you could buy a kilo of cocaine paste for $60 whilst you could sell cocaine in the US for $60,000.

In Renault 4s, Escobar proceeded to smuggle the paste across three countries (Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia). He had a separate Renault 4 for every country, and the paste was hidden in a compartment above the passenger’s-side wheel. The paste was then cooked into cocaine in a house with covered windows in a residential neighborhood. Escobar tried the cocaine himself, but preferred smoking marijuana.

Escobar quickly realized that he had underestimated the cocaine demand. If he wanted to, he could sell any amount to any country, especially the US. The US authorities were focused on marijuana and heroin being imported from Mexico, which was why it was relatively easy to smuggle cocaine.

Nevertheless, Escobar came up with ever-more ingenious ways of smuggling cocaine into the US. At first, up to 40 kilos of cocaine were packed into used airplane tires, which would be discarded by pilots in Miami. Later on, Colombian and US citizens would board flights with double-walled suitcases or hollowed-out shoes. Some even swallowed cocaine in condoms – if the condom opened, they died.

To keep the police happy, Escobar would regularly allow them to confiscate large amounts of cocaine, so that the officers would receive pay rises and promotions. They were also on Escobar’s payroll, so the cocaine was eventually returned to him, whilst being reported as destroyed. According to Attwood, “Corrupt governments all over the world still run this scam on US taxpayers.”

Eventually, Escobar moved his cocaine kitchens from residential areas to the jungle because of the smell. He also offered high rates of return and attracted many investors that way: if you invested $50,000, it would be repaid with $75,000 in two weeks.

George HW Bush and the CIA

While the Netflix series “Narcos,” focuses on the DEA’s (Drug Enforcement Administration) quest to capture Escobar, it fails to mention the CIA’s complicity in cocaine trafficking at the time. This may seem surprising, given the US’ strong opposition to drug use at the time.

In the 1980s, the Reagan-Bush administration launched a “Just say no” campaign, funded by tobacco, alcohol, and pharmaceutical companies. According to the government, it was necessary to take down “the Pablos of this world” but in fact, the anti-drug policies mostly affected hundreds of thousands of non-violent marijuana users, and more often than not, poor, black people.

Whilst Bush and Reagan were posing with tons of confiscated cocaine, the price for cocaine in America was falling, a sure sign that supply was increasing (something the Bush-Reagan government failed to mention). To top it all off, the federal government also used the highly toxic weed killer Paraquat to spray marijuana fields, a deadly toxin that kills animals and humans alike.

Escobar was a convenient enemy for the Bush administration, inaugurated in 1989, since after the fall of the Berlin Wall, the Communists did not pose an immediate threat anymore. Following Bush’s crackdown on drug use, twice as many people were arrested for possession than supplying in the US.

Nevertheless, at the same time, Bush was facilitating the import of cocaine via the CIA. Over dinner in 1985 with retired US Navy Lieutenant Commander Al Martin, Jeb Bush, and CIA veteran Felix Rodriguez, George HW Bush boasted that he operated on the Big Lie principle: “Big lies would be believed because the public couldn’t conceive that their leader was capable of bending the truth that far, such as a president railing against drugs while overseeing drug trafficking worth billions.”

At the time, Nicaraguan rebels were actually smuggling cocaine into the US using the same pilots, planes, and hangers as the CIA and National Security Council (NSC). To this day, the CIA still refuses to reveal any information it holds on Los Pepes (a group consisting of Escobar’s enemies) or on Escobar’s death.

Death

It is unclear how exactly Escobar found his end. After making millions in the drug trade, he had attracted many enemies. Some of these had bonded together in a group known as Los Pepes, threatening Escobar’s family. Another person who was hunting Escobar was Colonel Martinez, head of the Search Bloc. His son Hugo attempted to track Escobar down using CIA technology.

With the help of several vans parked on hills, a location could be triangulated. Hugo Martinez kept track of Escobar’s phone calls in an attempt to locate him. However, the CIA technology was new, and more often than not, Martinez tracked down the wrong signal.

Escobar was separated from his family and contacted them frequently. They were housed in a government building, fearing that Los Pepes would come and kill them at any moment. Escobar was hiding in a neighborhood in Medellín, Los Olivos. From there, he negotiated for his family’s safety with the government. He offered to surrender if his family was evacuated safely from the country first. They were flown to Germany but denied entry, and on their return, housed in a hotel in Bogotá without protection.

Escobar called his family even more often, worried for their safety, which led to his calls being tracked to Los Olivos. He also spent a long time in early December talking to his son, Juan Pablo, who was giving an interview to journalists. Escobar was so focused on making sure that his son would give the right answers to the press that he stayed longer on the phone than he would normally have.

Hugo Martinez managed to track his signal right down to his street and eventually saw Escobar standing at a top-story window. While Escobar tried to flee over the roof, he was shot through the leg, torso, and fatally through the ear. His family claims the shot through the ear was actually him committing suicide.

Escobar’s death did nothing to halt the cocaine trade into the US. The Colombian upper classes were happy about his death, but the poor were devastated. At his funeral, more than 5,000 rushed to touch his coffin, and his grave was protected by an armed guard for the first year after his death. According to Attwood, the parties who profited from Escobar’s death were “the banking, corporate and military interests represented by Bush.” Some of Escobar’s billions in Panama even ended up in George HW Bush’s hands.

Final Notes

“Narcos,” the Netflix series revolving around the life of Pablo Escobar, leaves out one crucial detail: the involvement of the George HW Bush administration and the CIA in the trafficking of cocaine. As Attwood suggests, they even benefited from Escobar’s death, while the cocaine trade into the US continues to soar.

Attwood writes from a former drug dealing background, and his book seems to be biased in favor of Escobar. He writes, at times, admiringly about a man who murdered, threatened, and tortured countless people and their families.

12min Tip

If you are interested in the War on Drugs, why not read “Chasing the Scream” by Johann Hari?