In the spring of 1996, 30 distinct expeditions were on the flanks of Everest, the highest mountain in the world. Jon Krakauer was a member of the most infamous one, and “Into Thin Air” tells his story. That’s right: get ready for a chilling firsthand account of one of the deadliest disasters in the history of climbing Everest.

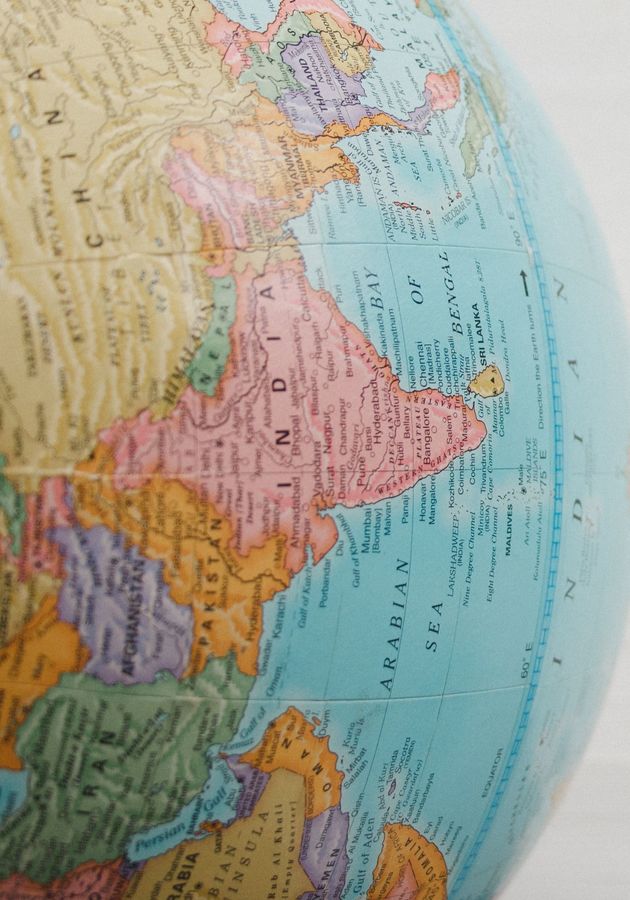

The Seat of God

In 1852, using trigonometric calculations, a brilliant Indian Bengali mathematician named Radhanath Sikhdar (Rad-han-ath Seek-dur) came to the conclusion that the so-called Peak XV of the Himalayas was the highest in the world, with a calculated elevation of exactly 29,000 feet above sea level, a number slightly revised by modern surveys to the currently accepted altitude of 29,028 feet, or 8,848 meters. In 1865, nine years after Sikhdar’s computations had been confirmed, Andrew Scott Waugh, the Surveyor General of India at the time, bestowed the name Mount Everest to Peak XV, in honor of his predecessor, Sir George Everest. Even then, however, the peak’s native names were much more descriptive. The Tibetans, living on the north of the great mountain, called it Jomolungma, or “Goddess, Mother of the World.” The Nepalis, residing on the south, used a name with similar connotations: Devadhunga, or “The Seat of God.”

It didn’t take long after Sikhdar’s finding for Mount Everest to become “the most coveted object in the realm of terrestrial exploration.” Gunther Oskar Dyhrenfurth (DEER-eh-furth), an early Himalayan explorer and an Olympic gold medalist in alpinism, once proclaimed that getting to the top wasn’t just a matter of pride, but “a matter of universal human endeavor, a cause from which there is no withdrawal, whatever losses it may demand.” It would require the superhuman efforts of 15 expeditions and th e lives of 24 individuals before the summit of Everest would finally be reached. Shortly before noon on May 29, 1953 – 101 years after Sikhdar’s discovery – Sir Edmund Hillary, a long-legged New Zealander, and Tenzing Norgay, a highly skilled and indomitable Nepalese mountaineer from the Sherpa mountain tribe, became the first humans to stand atop the world’s highest mountain.

Jon Krakauer, the author of “Into Thin Air,” was conceived merely a month later. Just like many other mountain climbers, amateur or professional, he grew up worshipping Hillary and Norgay and dreamed of one day repeating their feat. In 1996, he got the perfect chance to do it: Mark Bryant, the editor of Outside magazine, proposed that Krakauer join a guided Everest expedition and write an article about “the mushrooming commercialization of the mountain.” You see, for the three or so decades after Hillary and Norgay’s achievement, Everest had been “the province of elite mountaineers.” But then, in 1985, a wealthy 55-year-old Texan with limited climbing experience named Richard “Dick” Bass was “ushered to the top of Everest by an extraordinary young climber named David Breashears.” Thanks to “a blizzard of uncritical media attention,” the event became seminal in the history of guided climbing, spawning several high-altitude businesses. As a result, in the spring of 1996 alone, at least 10 distinct expeditions organized by money-making ventures were on the flanks of Everest. Krakauer was about to become part of the most notorious one.

The Adventure Consultants

In 1991, “convinced that an untapped market of dreamers existed with ample cash but insufficient experience to climb the world’s great mountains on their own,” Rob Hall and Gary Ball – two extraordinary New Zealand mountaineers – founded Adventure Consultants, a pioneer in guided climbing. The enterprise quickly became “the world leader in Everest Climbing,” with more successful ascents than any other similar organization. Just between its founding and 1996, the company organized seven expeditions and was responsible for putting 39 amateur climbers on the summit of Everest, without suffering a single fatality. Therefore, in the spring of 1996, it could charge a whopping $65,000 a head to guide clients to the top of the world, and still have no troubles filling a roster for the expedition.

In addition to the company’s founder Rob Hall (35 years old at the time) and author Jon Krakauer (42), the Adventure Consultants Guided Expedition of 1996 included the following members:

- Mike Groom, 37, an Australian guide.

- Andy “Harold” Harris, a likeable 31-year-old guide from New Zealand.

- Beck Weathers, 49, a garrulous and opinionated Texan pathologist.

- Stuart Hutchison, 34, a cerebral Canadian cardiologist with only a few previous 8,000m experiences; the youngest among the clients.

- John Taske, a 56-year-old Australian anesthesiologist, the oldest on the team, with no previous 8,000 m experiences.

- Frank Fischbeck, 53, an elegant Hong Kong publisher who had attempted Everest three times with other companies.

- Yasuko Namba, 47, a taciturn but ambitious Japanese personnel director, striving to become the oldest woman to climb Mount Everest and the second Japanese woman to climb all of the Seven Summits.

- Lou Kasischke (kah-sish-kee), 53, a gentlemanly American corporate attorney who, just like Namba, had climbed six of the Seven Summits before the expedition.

- Doug Hansen, 46, an American postal worker who had attempted climbing Everest with Hall’s team a year before the expedition, but was forced to turn back just meters from the peak due to an impending storm.

Unlike all the other members of the expedition, Hansen had a lower-middle-class background and could only pay the $65,000 fee with the help of a local elementary school who had organized a fundraiser to supply the money. Possibly because of this, Hansen was pretty much the only client with whom Krakauer – who wasn’t at all fond of the commercialization of Mount Everest – developed a deeper bond at the beginning of the Everest climb. Little could he have guessed that by the end of it, his life would become inextricably linked with those of every other member of the Adventure Consultants Guided Expedition of 1996.

Mountain Madness at the Everest Base Camp

On the southern side of Mount Everest in Nepal, at an altitude of 17,600 feet (about 5,360 meters), there is a base camp. It is a rudimentary assembly of supply-storing tents and temporary structures, and serves as the staging ground from which all Everest summit bids set out. The Adventure Consultants, joined in the meantime by eight highly skilled Sherpas led by their sirdar Ang Dorje, reached the base camp on April 12, 1996, the day of Krakauer’s 42nd birthday. This was an enormous achievement in itself, but, in many ways, it was merely the beginning of the real and tortuous ascent to the top.

At Base Camp, Krakauer got the chance to get acquainted with the other teams attempting to conquer Everest around the same time as his. One of the teams, called Mountain Madness, was led by a 40-year-old American named Scott Fischer, a friendly rival of Hall in the mountaineering business. Unlike the highly organized and studious Hall, the charismatic and well-liked Fischer was known for his laid-back and easygoing approach to climbing. He had tried recruiting Krakauer himself for the expedition, but Hall offered Outside magazine a better deal. Rather than despair, Fischer enlisted Sandy Hill Pittman, a 41-year-old “millionaire socialite-cum-climber” back for her third attempt on Everest. Pittman had made an agreement with NBC to do a daily video blog about the ascent, which meant that parts of it were streamed live to American schoolchildren.

Two years before the 1996 expedition, Fisher had made a name for himself for summiting Mount Everest without the help of supplemental oxygen. His guide, the extremely talented 38-year-old Russian climber Anatoly Boukreev (Anna-toll-ee Bou-Kray-ev), had already achieved the same feat twice. However, unlike Fischer, Boukreev was anything but a people person. In fact, he was outspoken about his lack of interest in pampering Fischer’s clients, firmly believing, in his broken English, that, “if client cannot climb Everest without big help from guide, this client should not be on Everest.”

The Adventure Consultants and the Mountain Madness were only two of the several expeditions trying to climb Everest in the spring of 1996. Among others, there was also an accident-prone Taiwanese team, led by a man named “Makalu” Gau Ming-ho, and the Johannesburg Sunday Times Expedition, headed by an unlikable and loquacious 39-year-old “control freak” named Ian Woodall, whose dictatorial character had caused three experienced South African climbers to resign from his team by the time they had arrived the Everest Base Camp. Finally, there was an IMAX team as well, shooting “a $5.5 million giant-screen movie about climbing the mountain,” headed by David Breashears, the same man who had guided Dick Bass to the Everest summit in 1985. In addition to being a respected climber, Breashears was also a talented filmmaker. Arguably, that’s how he is best remembered today: as the director of “Everest,” the highest-grossing IMAX documentary ever made. Not the least because the film would come to include the footage of a disaster.

Laying siege to the mountain

In the words of Krakauer, ascending Everest from Base Camp to the top is “a long, tedious process, more like a mammoth construction project than climbing.” Indeed, ever since English mountaineer George Leigh Mallory devised it in the early 1920s, the strategy of most Everesters has remained the same to this very day: to “lay siege to the mountain.”

Once the teams had reached the Everest Base Camp, the Sherpas in Hall’s and Fischer’s expedition were sent to establish a series of four fully stocked camps to serve as intermediate stops on the journey. Each of these camps was set up approximately 2,000 feet (600 meters) higher than the last, with the highest camp – Camp Four – set at an altitude of 26,000 feet (about 8,000 meters) on the famous South Col, a sharp-edged low point between Mount Everest and another high Himalayan peak. If all went according to Hall’s plan, the Adventure Consultants were supposed to launch their summit assault from this highest camp on May 10, about a month after reaching the Everest Base Camp.

During this month, as the Sherpas were “shuttling cumbersome loads of food, cooking fuel, and oxygen from encampment to encampment,” members of all teams were required to make “repeated forays above Base Camp” to acclimatize to the high altitude. Put simply, human beings aren’t built to function at certain heights. Even at Base Camp, climbers sometimes start suffering from acute mountain sickness, feeling dizzy, nauseous, confused and even dehydrated. But that’s nothing compared to what might happen to an individual beyond the South Col, a territory justly termed “the Death Zone.” Namely, at altitudes above 26,000 feet (8,000 meters), most humans are at risk of developing High Altitude Pulmonary Edema, or HAPE, “a mysterious, potentially lethal illness typically brought on by climbing too high, too fast in which the lungs fill with fluid.”

Unfortunately, that’s precisely what , a veteran Sherpa on the Mountain Madness team, came down with on April 16, during one of his team’s acclimatization runs to Camp Two. Lopsang Jangbu, Ngawang’s nephew and Fischer’s 23-year-old climbing sirdar, was left especially shaken by the event. Just like many other Sherpas, he blamed Topche’s fatal disease on the behavior of an unidentified female member of the Mountain Madness team (probably socialite Sandy Pittman) having extramarital sex with a member of another expedition. “Mount Everest is God – for me, for everybody,” Lopsang solemnly told Krakauer two and a half months after the expedition. “Just husband and wife sleep together, is good. But when [X] and [Y] sleep together, is bad luck for my team[…] The first day [X] and [Y] in tent, just after, Ngawang Topche is sick at Camp Two. So, he is dead now.”

Assaulting the summit

Following the month-long acclimatization period, at around 4:30 a.m. on May 6, 1996, the Adventure Consultants commenced their bid for the summit, planning to reach Mount Everest about four days later. At Hall’s suggestion, they decided to enforce a strict “two o’clock rule,” stating anyone who wasn’t within spitting distance of the summit by 2 p.m. on May 10 had to turn around and go down, no questions asked or pleading allowed. After all, as Krakauer writes, “above the South Col, up in the Death Zone, survival is to no small degree a race against the clock. Upon setting out from Camp Four on May 10, each client carried two 6.6-pound oxygen bottles and would pick up a third bottle on the South Summit from a cache to be stocked by Sherpas. At a conservative flow rate of two liters per minute, each bottle would last between five and six hours. By 4:00 or 5:00 P.M., everyone’s gas would be gone.”

However, Krakauer was the only member of Hall’s team to make it to the summit of Everest before the suggested cutoff time. He was also one of only three paying clients to reach the top before 2 p.m., the other two being Martin Adams and Klev Schoening, members of the Mountain Madness team. Fischer’s guides, Boukreev and Neal Beidleman, as well as Hall’s guide Andy Harris, were also there on time. All the others appeared afterward. Some – such as guides Rob Hall, Lopsang Jangbu, and Mike Groom, and clients Sandy Pittman and Yasuko Namba – weren’t late by much. Others, however, such as Fischer and Hansen, reached the top long after they were supposed to, at around 4 p.m.

By then, however, Krakauer had already turned back, rushing to reach Camp Four before an impending storm. Moreover, just like most of the other members, he was running low on oxygen. On his way back to the South Col, he happened upon Beck Weathers, the Texan pathologist, trapped in the blizzard and virtually blind due to the worsening of a preceding eye condition, courtesy of Mount Everest’s merciless climate. Believing guide Mike Groom to be behind him and better equipped to help Weathers, Krakauer left his fellow climber alone in the snowstorm. By 6 p.m., he managed to reach Camp Four, exhausted and barely able to think clearly due to oxygen deprivation. Little could he have guessed that most of his peers and teammates were fighting for their lives at the time, not too high above his tent, on the snowy slopes of the indomitable mountain.

Lost and found

Soon after Krakauer headed back for Camp Four, Mountain Madness junior guide Neil Beidleman decided he couldn’t wait for his superior Scott Fischer anymore and began descending with five of the company’s clients, including Pittman. Eventually, the six climbers ran into Adventure Consultants guide Mike Groom, struggling to support Yasuko Namba and Beck Weathers, both in serious and gradually deteriorating health conditions. Though moving extremely slowly, by 6:45 p.m., the two groups – now coalesced into a single team – descended to within 200 vertical feet of Camp Four. However, by then the night had fallen and the blizzard had grown too intense, so they couldn’t locate the tents and instead kept staggering around blindly in the storm. After wandering aimlessly for two hours, they decided to huddle up and wait for a break in the storm.

Fortunately, that happened several hours later. Forty-five minutes after midnight, Beidleman, Groom and two Mountain Madness climbers hobbled into Camp Four, where Boukreev had been eagerly awaiting them for hours. Having left the summit around 2 p.m., the Russian had arrived at Camp Four well before the storm. As time went by, his concern about his missing teammates grew from a bad feeling to an all-consuming, gut-wrenching fear. Having regained some strength, at around 7:30 p.m., Boukreev even went to search for the group on his own, but, due to poor visibility, he very nearly became lost himself. But now, Beidleman and Groom – though barely able to speak – gave Boukreev the general location where to search for the rest. So, the Russian went on another brave rescue mission. This one wasn’t as futile as the first: by 4:30 a.m., he managed to save the lives of several climbers, including the nearly dead Sandy Pittman.

Unfortunately, he couldn’t rescue Weathers and Namba, both of whom he determined to be in a condition “beyond saving.” Soon after, a team of four Sherpas organized and led by Hall’s client Stuart Hutchison stumbled across the bodies of Weathers and Namba and came to the same conclusion. They shared it with Krakauer and the rest at Camp Four and everybody agreed with the agonizingly difficult decision to leave Beck and Yasuko behind and save the group’s resources for those who could actually be helped. “Even if they survived long enough to be dragged back to Camp Four,” Krakauer explains, “they would certainly die before they could be carried down to Base Camp, and attempting a rescue would needlessly jeopardize the lives of the other climbers on the Col, most of whom were going to have enough trouble getting themselves down safely.”

Leaderless and hopeless

The reason why Stuart Hutchison, a client with limited mountaineering experience, had to organize the rescue mission for Weathers and Namba was this: on the morning of May 11, 1996, the Adventure Consultants woke up scared, traumatized – and leaderless. Having barely survived the storm from the night before, their junior guide, Mike Groom, was “seriously frostbitten, lying insensate in his tent.” Far worse, their other two guides, Andy Harris and Rob Hall, were missing. It’s difficult to say precisely what happened to them but the most probable timeline looks like this.

At around 3 p.m. on May 10, Ang Dorje Sherpa, while climbing down from the summit, came across American postal worker Doug Hansen and ordered him to descend. Refusing to turn back for a second year in a row just a few hundred meters away from Everest, Hansen allegedly shook his head and pointed upward. With the help of Hall, Hansen eventually reached the summit. By then, however, he was too exhausted to go back. Not wanting to leave him behind, Hall called Andy Harris requesting emergency oxygen.

Despite being already 5 p.m., Harris – who might have been suffering from hypoxia at the time and not thinking clearly – hiked back up the mountain to assist Hall and Hansen. Nobody heard from the three until 4:43 a.m. the following morning when Hall radioed the Everest Base Camp, informing them of his location and the deaths of his fellow climbers. Hall also told Caroline Mackenzie, the Base Camp doctor, that he was “too clumsy to move” and that his legs no longer worked. A rescue mission was sent immediately, but due to high winds it had to turn around. Hall’s friends and teammates spent the entire day begging him to make an effort to come down a little lower under his own power, but it was to no avail: he just couldn’t.

Later in the afternoon, Hall called again with a request to be patched through to his pregnant wife, Jan Arnold, on the satellite phone. During the conversation, Hall assured Jan that he was “reasonably comfortable” despite having a bit of frostbite. “I love you,” he told her before signing off. “Sleep well, my sweetheart. Please don’t worry too much.” These were the last words anyone would ever hear Hall utter. Later attempts to make radio contact with Hall went unanswered. Twelve days afterward, David Breashears and his IMAX teammate Ed Viesturs found Rob Hall’s body buried beneath a drift of snow. It is still there, just below the South Summit of Mount Everest.

Survivors and survivor’s guilt

Hall wasn’t the only expedition leader to go hors de combat on Everest in the spring of 1996. The same happened to the leader of the Taiwanese team, Makalu Gau, as well as Hall’s friendly rival, Scott Fischer. Extremely weak and oxygen-deprived, both of them stopped descending around 8 p.m. on May 10 and called to ask for a rescue mission. However, by the time a Sherpa team located the two the following day, only Gau was conscious enough to be rescued. Later on, Boukreev made another attempt to save Fischer, but he only found his frozen, lifeless body covered by the snow.

In the meantime, as they were preparing to climb down, the surviving members of the Mount Everest expedition were treated to a truly miraculous sight: Beck Weathers, left for dead in the storm, somehow found the strength and awareness to stumble back to Camp Four on his own, after having spent an entire night in an open bivouac, with his face and hands exposed to the elements and the subzero wind. When Krakauer found him in his tent, he didn’t know what to do. Weathers looked all but dead, “lying on his back across the floor of his collapsed shelter, shivering convulsively. His face was hideously swollen; splotches of deep, ink-black frostbite covered his nose and cheeks.”

Nobody expected for Weathers to survive another night on Everest; almost inexplicably, he did. On May 12, as soon as the storm had passed, a helicopter arrived to take him and Gau to the nearest hospital. In the meantime, the rest of the group began their descent down the mountain. On the morning of May 13, they reached Base Camp. Finally safe, Krakauer sat down on the ice and buried his face in his hands. Tears started streaming down his cheeks. “I cried for my lost companions,” he remembers, “I cried because I was grateful to be alive, I cried because I felt terrible for having survived while others had died.”

Indeed, many had died: four members of the Adventure Consultants expedition (Yasuko Namba, Doug Hansen, Andy Harris and Rob Hall), and the leader of the Mountain Madness team, Scott Fischer. For a while, Krakauer couldn’t find the strength to write his commissioned article for Outside magazine. When the article finally appeared (in September 1996), it immediately angered many friends and relatives of the Everest victims. To clear things up, Krakauer decided to expand the article into this book. To this day, however, he still struggles with survivor’s guilt.

Final notes

Exact details of the 1996 Mount Everest disaster remain unclear to this day due to conflicting accounts provided by the survivors. For many reasons, however, Krakauer’s account is still the most famous and most commented one.

Leaving controversies aside, whether you read it as a work of reportage or an adventure novel, “Into Thin Air” tells a riveting, harrowing and moving story – as bone-chilling and as haunting as only a few others.

Highly recommended.

12min tip

Compare Krakauer’s account with those by Anatoli Boukreev (“The Climb”), Beck Weathers (“Left for Dead”), and Lou Kasischke (“After the Wind”). Also, try to find and watch the IMAX documentary “Everest” (1998), as well as the same-titled 2015 Hollywood movie, starring Jake Gyllenhaal, Josh Brolin, and Keira Knightley.