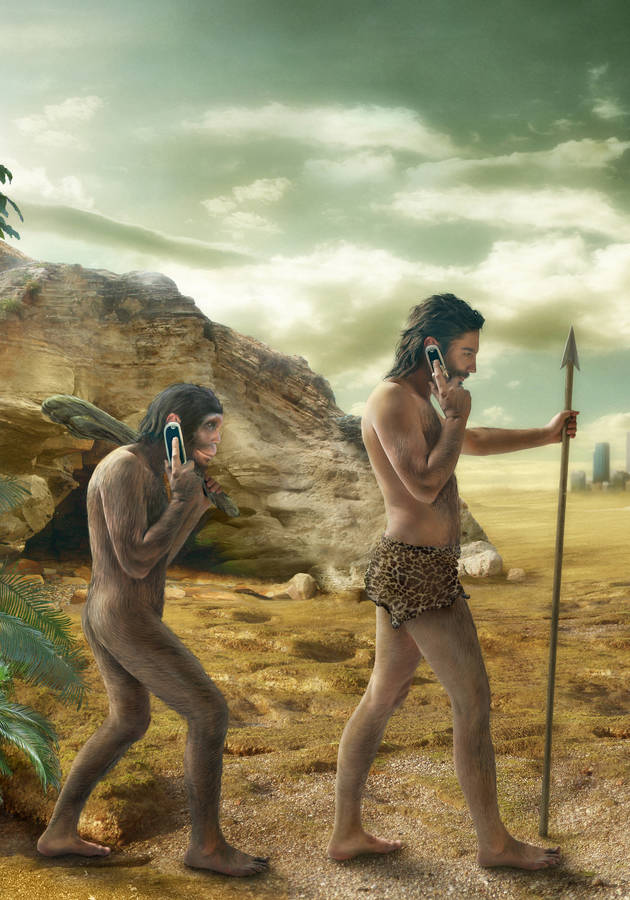

As of 2020, “A Random Walk Down Wall Street,” first published in 1973, has gone through 12 editions. Its basic thesis has remained the same throughout all of them: “that the market prices stocks so efficiently that a blindfolded chimpanzee throwing darts at the stock listings can select a portfolio that performs as well as those managed by the experts.” In other words, you don’t have to be a Wall Street professional to earn money from investing; in fact, in more ways than one, it’s even better if you are not. Burton G. Malkiel is here to explain why. So, get ready to join him on “a guided tour of the complex world of finance” and prepare to learn a thing or two on investment theories and strategies.

Random walks, firm foundations and castles in the air

As defined by Malkiel, “a random walk is one in which future steps or directions cannot be predicted on the basis of past history.” By way of analogy, in the world of finance, a random walk means that “short-run changes in stock prices are unpredictable.” That makes the phrase quite obscene to the ears of Wall Street experts because it implies that they are practically useless and that all of their attempts at predicting the fluctuations of the market are personal opinions, guesstimates at best. Dismissing foul play, the reason why some of them are rich – nay, filthy rich! – can’t be anything other than pure luck.

Of course, the pros in the investment community couldn’t agree less with this academic assessment. To counter it, they explain their efforts and successes through one of the following two models of investing:

- The firm-foundation theory argues that whether stocks or pieces of real estate, all investment instruments have “intrinsic value” – that is, a firm anchor of worth. This intrinsic value can be determined by a careful and thorough analysis of present conditions and future prospects, which is what investing should be all about. Opportunities for buying or selling stocks arise when market prices fall below or rise above this firm foundation of intrinsic value because the fluctuation will eventually be corrected. Thanks to the books of Benjamin Graham and David Dodd, there are many famous proponents of the firm-foundation theory of investing, the most successful among them being “the sage of Omaha,” Warren Buffett.

- The castle-in-the-air theory of investing – less charitably known as the “greater fool” theory – concentrates on psychic values. Most lucidly explained – and practiced – by John Maynard Keynes, the theory proposes that even if it was possible to estimate the intrinsic value of a stock (in which its proponents don’t believe), it would always be far more rewarding to analyze how the crowd of investors is likely to behave in certain situations. In investing, Keynes suggested, there is no reason, only mass psychology. In periods of optimism, which come in cycles, the crowds “tend to build their hopes into castles in the air,” so the job of a successful investor is to try to beat the gun “by estimating what investment situations are most susceptible to public castle-building and then buying before the crowd.” Nobel Prize winners Robert Shiller and Daniel Kahneman are some of the many advocates of this theory.

The madness of crowds and the sanity of institutions

Another famous proponent of the castle-in-the-air theory was economist Oskar Morgenstern, who believed that, as a constant reminder of their mission, all investors should keep the following La r desks: “A thing is worth only what someone else will pay for it.” His advice has history on its side – the sheer number of financial manias and speculative bubbles caused by the irrationality of the crowds is staggering. These two are the most famous:

- The tulip bulb craze. Generally considered the first recorded speculative bubble in history, the tulip-bulb craze took place in the first decades of the 17th century in the leading financial power of the world, the Dutch Republic. At the peak of the tulip mania – between 1634 and 1637 – tulip bulb prices reached such astronomic levels that people started bartering their personal belongings – such as land, jewels and furniture – to obtain them. Many lost everything when the prices dramatically collapsed in February 1637.

- The South Sea bubble. A little less than a century later, in 1711, the British government granted a monopoly to the South Sea Company to supply African slaves to South America. However, since Spain and Portugal controlled the continent at the time, there was never a realistic prospect that any trade would take place. It didn’t matter; thousands invested in the company whose stock dramatically rose over the following decade and then as dramatically collapsed in 1720. One of the investors who lost millions in today’s dollars in the South Sea bubble was Isaac Newton, arguably the greatest mathematician of all time. Afterward, he is alleged to have said: “I can calculate the motions of heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people.”

And indeed, how do you calculate irrationality? It is, by definition, illogical. No matter what castle-in-the-air investors say, predicting what other people would pay for something may be even more difficult than deducing its intrinsic value. Case in point: during the 20th century, numerous professional institutions fell victim to speculative bubbles. “In each case,” comments Malkiel, “professional institutions bid actively for stocks not because they felt such stocks were undervalued under the firm-foundation principle, but because they anticipated that some greater fools would take the shares off their hands at even more inflated prices.”

Technical and fundamental analysis

The two theories of investing come with two different types of analysis: technical and fundamental.

- Technical analysis is “the method of predicting the appropriate time to buy or sell a stock used by those believing in the castle-in-the-air view of stock pricing.” Technical analysts – also called technicians or “chartists” – believe that only 10% of the market is logical, the rest of it being psychological. Consequently, most of them don’t even bother checking the financial web services or the newspaper; they mostly charter “the past movements of common-stock prices and the volume of trading to predict the direction of future changes.” In a way, that makes their philosophy quite ambiguous and tautologica st of their most common prescriptions platitudes: “Buy when others buy, sell when they sell,” “Hold the winners, sell the losers,” “Switch into the strong stocks,” “Sell this issue, it’s acting poorly,” “Don’t fight the tape.” According to Malkiel, despite all their charts, anxieties and stresses, technicians don’t do better than exponents of the buy-and-hold strategy. Computer analysis has uncovered why, demonstrating that though history does tend to repeat itself in the stock market, it does so in “an infinitely surprising variety of ways that confound any attempts to profit from a knowledge of past price patterns.”

- Fundamental analysis falls into the firm-foundation school and seeks to determine the proper intrinsic value of a stock, caring little about past price movements. At odds with chartists, fundamentalists believe the market is 90% logical and only 10% psychological. Consequently, they also believe that careful analysis of a company’s past performance – obtained through public information that may be contained in balance sheets, income statements, dividends, etc. – is a good indicator of overall health and deviations, since it allows one to deduce the intrinsic value of a stock. They feel this is everything they need to know about whether a stock is undervalued or overvalued and whether it will go up or down in the future. The problem with fundamental analysis is that it tends to overestimate the validity of publicly available information and underestimate the effects of incompetence and corruption, creative accounting and conflicts of interest.

The efficient market hypothesis and three giant steps down Wall Street

If both technical and fundamental analysis don’t work, then what does? Malkiel says, quite simply, the market. Since prices convey information – and since new information arrives quite quickly and randomly – nobody can beat the market in the long run. This is not because it is too rational or too irrational, but simply because it is efficient by design. “The market is so efficient – prices move so quickly when information arises – that no one can buy or sell fast enough to benefit,” writes Malkiel. “And real news develops randomly, that is, unpredictably. It cannot be predicted by studying either past technical or fundamental information.”

This is the basis of the efficient-market hypothesis (EMH), of which Malkiel is one of the best-known modern proponents, and upon which he suggests one should build their own investment strategy. He is not alone; during the past few decades, even some of the most famous fundamentalists have joined his ship. For example, both Peter Lynch and Warren Buffett have recently admitted that “most investors would be better off in an index fund rather than investing in an actively managed equity mutual fund.” If you want to buy stocks and not lose money in the process, you don’t need Wall Street – you need to take three giant steps away from it:

1.The no-brainer step: investing in index funds. “The logic behind this strategy,” writes Malkiel, “is the logic of the efficient-market hypothesis. But even if markets were not efficient, indexing would still be a very useful investment strategy. Since all the stocks in the market must be owned by someone, it follows that all the investors in the market will earn, on average, the market return. The index fund achieves the market return with minimal expenses.”

2.The do-it-yourself step: potentially useful stock-picking rules. Above-average earnings require above-average risks. In his words, Malkiel’s four rules for successful stock selection are the following:

- Confine stock purchases to companies that appear able to sustain above-average earnings growth for at least five years.

- Never pay more for a stock than can reasonably be justified by a firm foundation of value.

- It helps to buy stocks with the kinds of stories of anticipated growth on which investors can build castles in the air.

- Trade as little as possible.

3. The substitute-player step: hiring a professional Wall Street walker. If you can’t beat them, they say, join them. In other words, if you don’t want to bother with picking winners, bother with picking coaches instead. Buying index funds is still better, but there are a few active mutual-fund managers with long-term records of successful portfolio management. Of course, the more successful they are, the more money you’ll pay them. And as Jack Bogle, the founder of the Vanguard Group, says, in the mutual fund business, “you get what you don’t pay for.”

Final Notes

In 2007, following the ninth edition of “A Random Walk Down Wall Street,” Paul B. Brown wrote the following in his New York Times review: “If one of your New Year’s resolutions is to improve your personal finances, here’s a suggestion: instead of picking up one of the scores of new works flooding into bookstores, reread an old one: ‘A Random Walk Down Wall Street.’”

Six years and one edition later, Los Angeles Times columnist Michael Hitzlick was even more effusive in his praises. Burton Malkiel, he wrote, “should be dipped in gold and placed on a pedestal in front of the New York Stock Exchange.” He ended his column the same way we will our summary: “Do you want to do well in the stock market? Here’s the best advice: scrape together a few bucks and buy Burton Malkiel’s book. Then take what’s left and put it in an index fund.”

12min Tip

Buying and holding index funds is the most effective portfolio-management strategy – and, over longer periods of time, will always trump buying and holding individual securities or actively managed mutual funds.